Understanding corruption and social norms: A case study in natural resource management

By Richard Nash, Cheyanne Scharbatke-Church, Zita Toribio, Peter Woodrow, Derick W. Brinkerhoff.

Open Access Peer Reviewed

DOI: 10.3768/rtipress.2023.op.0089.2309

Abstract

Corruption undermines many outcomes across development sectors, yet little is known about how social norms drive corruption or undermine anticorruption efforts in sector work. The conservation sector is no exception. The current study examined corruption and social norms related to infrastructure investments and site planning decisions and their subsequent effect on conservation outcomes. The study focused on the Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park, one of four protected areas under the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Sustainable Interventions for Biodiversity, Oceans and Landscapes (SIBOL) project in the Philippines, implemented by RTI International. The study was undertaken through a partnership between RTI and Besa Global. Based on a site visit, key informant interviews, and extensive document analysis, our findings elucidate a unique governance structure that enabled project partners to navigate the significant corruption risks present. Direct social norms were not found to be driving corrupt decision making. However, indirect norms played a role by dictating inaction or silence—powerful behaviors—in the face of abuse of entrusted power for personal gain. Our analysis highlights the challenges and importance of having practitioners clearly define and understand what they mean by “corruption” as well as the importance of undertaking a systems analysis that incorporates the influence of social norms on behaviors within that system.

![]() © 2025 RTI International. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

© 2025 RTI International. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Contents

Understanding Corruption and Social Norms: A Case Study in Natural Resource Management

Introduction

Corruption undermines all sectors and development outcomes. It erodes trust in democracy, deters foreign investment, acts as a recruitment stream for extremists, and in the worst cases, supports regimes that actively repress their citizens. For more than 20 years, donors, governments, civil society, and individuals worldwide have adopted numerous approaches to prevent and counter corruption. There have been many successes, but in too many countries, corruption continues to be a significant and evolving problem. Even before a new “solution” to address one aspect of corruption is fully implemented, those behind corrupt schemes have often adapted and moved on to new schemes.

There is no internationally agreed-upon definition of “corruption.” In recent years, development practitioners have broadly coalesced around the Transparency International (n.d.) definition: “The abuse of entrusted power for private gain.” The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) used this definition until late 2022, when the organization updated it to “the abuse of entrusted power and influence for personal or political gain” (USAID, 2022).

Within academia, a specialized definition of corruption in natural resource management has been proposed by Paul Robbins (2000): “a system of normalized rules, transformed from legal authority, patterned around existing inequalities, and cemented through cooperation and trust.” Robbins’s definition of corruption has several key distinctions, such as treating corruption as a “system” in which a series of interconnected factors produce specific behaviors over time. Corruption must be understood as being embedded within wider social dynamics.

At the international level, the United Nations Convention Against Corruption does not include a definition of corruption but instead enumerates a series of activities conducted by public officials that state parties must pass legislation to criminalize (e.g., bribery).

For the purposes of this study, the research team used USAID's definition of corruption as the basis of investigations.

There is a vast amount of scholarship examining corruption and strategies to combat it. The dominant theoretical frame within this scholarship posits that corrupt practices result from the monopoly of people with decision-making power in a country or sector with little to no accountability (Klitgaard, 1988). In response, anticorruption programs have typically used one of three strategies: first, increasing the transparency and accountability of government activities and decision-making processes; second, increasing participation and inclusion of citizens in decision-making processes; and third, improving sanctions and enforcement approaches by supporting independent anticorruption agencies as well as making broader investments in specialized criminal law approaches with the police, prosecutors, and courts to respond to corruption. In turn, donor programs have focused on top-down legal and governance system strengthening and bottom-up civil society “watchdogs” (see, for example, Department for International Development, 2015; USAID, 2014; or Brinkerhoff, 2010).

Despite the significant investment in these strategies, donors, academics, and civil society are increasingly concerned that the effectiveness of these approaches is limited, especially in fragile states. Researchers have proposed several alternative approaches (see, for example, Jackson, 2020), one of which is founded on the premise that corruption is a systemic problem requiring broad-based collective responses. Similarly gaining traction are integrated approaches to corruption that address not only compliance, enforcement, and transparency approaches but also broader political economy and social science understanding of why corrupt systems are so resilient and hard to change. Within corrupt systems are social norms—the unspoken and informal behavioral rules shared by people in a given society/group that define what is considered appropriate behavior—that serve to drive, or even enforce, corrupt actions (see Scharbatke-Church & Chigas, 2019, and Baez Camargo & Kassa, 2017). Social norms are experiencing a moment in the spotlight but viewing corruption through a social norms lens is far from a tried and tested strategy.

This paper summarizes the results of a case study that was undertaken to better understand how social norms drive corrupt practices. To increase utilization of the results, the case site selection was performed in conjunction with the ongoing USAID Sustainable Interventions for Biodiversity, Oceans and Landscapes (SIBOL) program in the Philippines. The questions explored included:

What, if any, corrupt acts were undermining the project’s outcomes?

What social norms might be driving these actions?

What could the project do about them?

The case study contributes to the practice gap in the field by explaining the process of investigating these issues as well as the lessons learned for others to draw upon. We first provide a brief overview of social norms as the conceptual foundation for the case study. Next, we explain our methodology and case selection and then present and discuss the findings from our research, followed by our core lessons learned.

Social Norms

There are many factors an individual considers, implicitly and explicitly, when making choices about how to act. These commonly include the law, feelings of self-efficacy, aspirations, economic options, and values, as well as social norms which are the mutual expectations within a group about the right way to behave. Social norms represent what a group of people accept as appropriate and typical behaviors and are enforced—to varying degrees—by the group itself.

Social norms can either be “direct” or “indirect” (Cislaghi & Heise, 2018). Direct social norms are the unwritten rules about the right way to behave within a group. These rules take the form of mutual expectations about what is appropriate and typical behavior for that group in a particular context and are held in place through positive and negative sanction (Scharbatke-Church & Chigas, 2019). Indirect social norms are mutual expectations about the right thing to do in a particular situation that manifest in a range of behaviors, thus acting more like principles rather than specific directives.

Direct social norms are made up of descriptive and injunctive beliefs. Descriptive norms or beliefs are what one perceives others in their group to do in a particular situation. Injunctive norms are what one perceives others in their group think they should do.

Norms differ from behaviors because behaviors are acts performed by individuals and are not beliefs or attitudes (Scharbatke-Church & Chigas, 2019). These behaviors are influenced by a variety of factors, including social norms, but also by attitudes, circumstances, values, abilities, etc. (Cislaghi & Heise, 2016). Regularized or habitual behaviors are those that are commonly conducted by people.

Social norms matter because they are a significant influence on behavior. In fact, studies show that social norms can influence decisions more than individual attitudes or laws (Chang & Sanfey, 2013). Research in other fields (e.g., public health and gender) has found social norms to act as a brake on the behavior change sought by a program (Heise & Manji, 2016). In other words, even if one can change the technical factors, such as legal loopholes, that drive a particular corrupt behavior, sustainable shifts are out of reach without norm change.

Sanctions—both positive and negative—enforce social norms (Bicchieri, 2016). Those who comply with the group’s expectations receive subtle, positive reinforcements (e.g., smiles, nods, approval), and those who do not are negatively sanctioned, typically through social means (e.g., rumors, cold shoulder). However, sanctions are not always only “social” in nature. Where members of the group (e.g., supervisors) also possess official power, they also may give professional rewards (e.g., training opportunities or promotion) and consequences (e.g., demotion, being side-lined or transferred) (Miller, 2023). In these environments, social norms may be more appropriately labeled “workplace” norms, which are the mutual expectations within a workplace about the right way to behave.

The distinction between the two forms of social norms—direct and indirect (see the “Key Terms on Social Norms” text box)—is important, because it impacts how one might support a norm change in relation to corrupt behaviors.

Direct social norms dictate a specific behavior. For direct norms, mutual expectations require a specific action. For instance, doctors might be expected by other doctors to demand a fee for service from patients, even if the service is legally free.

Indirect social norms can manifest in a variety of actions. Indirect norms act more like principles, and there are numerous behaviors that could be deemed appropriate to fulfill expectations. For instance, the expectation that members of a militia should be loyal to each other could result in a range of behaviors, such as physical protection or refusal to provide information on a fellow member to the authorities.

Methodology

In this paper, we summarize the results of a study conducted in partnership between RTI, the Corruption, Justice and Legitimacy (CJL) Program, and USAID’s SIBOL program in the Philippines (SIBOL is implemented by RTI). This research was motivated by the increasing interest among anticorruption practitioners in the potential of social norms as drivers of corrupt practices and blocks to anticorruption efforts. Although there has been much academic debate and interest in this area (Jackson & Köbis, 2018), there have been very few applied research studies working directly with projects to date; this effort sought to contribute to the practice gap.

SIBOL works to strengthen the governance of key natural resources by clarifying authority and coordination—both nationally and at a site level—to understand the political climate and current political practices. SIBOL also strengthens land and coastal resource management by supporting the effective participation of communities and other underrepresented groups in governance structures, as well as by developing cutting-edge decision-making tools to improve biodiversity and socioeconomic monitoring and analysis.

USAID recognized during the SIBOL program design process that weak natural resource governance feeds corruption, hinders effective management, and minimizes efforts to reduce environmental crime. For instance, there are limited mechanisms to resolve contested claims in the Philippines. Moreover, the mandate and authority of protected area management board (PAMB) members are unclear, causing inaction and noninclusive engagement of local natural resource user groups and communities. The study sought to offer SIBOL decision makers further insights into the corruption dynamics within PAMB decision making to inform the ongoing program and to develop a case study from which broader lessons learned could be extracted for the wider practitioner community working on these issues.

The research team consisted of CJL, RTI, and SIBOL staff as well as a conservation specialist from the Philippines. Our first step was to align our research question to our resources and to consider the ongoing uncertainty generated by COVID, which resulted in limiting our inquiry to the PAMB decision-making mechanisms. This offered a feasible, yet important, focus to the case.

Next, we identified which site within the four protected areas (PAs) under the SIBOL project to study. Focusing on a single PA allowed the research team to understand the specific corruption problem that social norms might be driving. In CJL’s experience, corrupt systems may appear similar across a country, but there are local nuances, particularly in the way norms are exhibited within reference groups. These nuances become important to understand if one is planning to develop a robust theory of change with locally grounded assumptions.

Criteria for PA selection included: perception of the existence of regularized corrupt practices, access to the PAMB and key actors in the area, and the capacity of the SIBOL local office to support the research. To gain a better understanding of the types of corruption and where they were happening in the PAs, the research team conducted a virtual focus group with members of the SIBOL team, followed up by remote interviews with key informants from that group. Simultaneously, the research team conducted a rapid literature review to provide a baseline for understanding how corruption manifests in the Philippines as well as in natural resource management.

Based on the conversations with SIBOL members, the research team chose the Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park (PPSRNP). There was anecdotal evidence and references in open-source literature that corruption was undermining effective conservation outcomes at PPSRNP (Global Witness, 2019). Further, SIBOL had a high-functioning team in Puerto Princesa that had excellent relationships with the PAMB and its support office, the Protected Area Management Office (PAMO).

The site selection process highlighted several gaps in knowledge around the corruption dynamics within decision-making processes of the PPSRNP. Specifically:

To what degree were there issues of regularized corrupt practices within the PAMB decision-making process?

If there were examples of regularized corrupt practices, what was the influence of social norms?

To answer the first question, the Philippines researcher reviewed PAMB meeting minutes and conducted 21 qualitative interviews with key PPSRNP informants (which included a mix of people from government, civil society, the larger local community, the Indigenous community, and the private sector). The review analyzed 3 years of decisions around a broad range of projects, investments, and business enterprises (private or government owned or operated) that use land, water, and other significant natural resources in ways that have the potential for major conservation impacts within the PA. The researcher’s inquiry focused on identifying deviations from the official processes and rules governing PAMB decisions on investments and projects within PPSRNP.

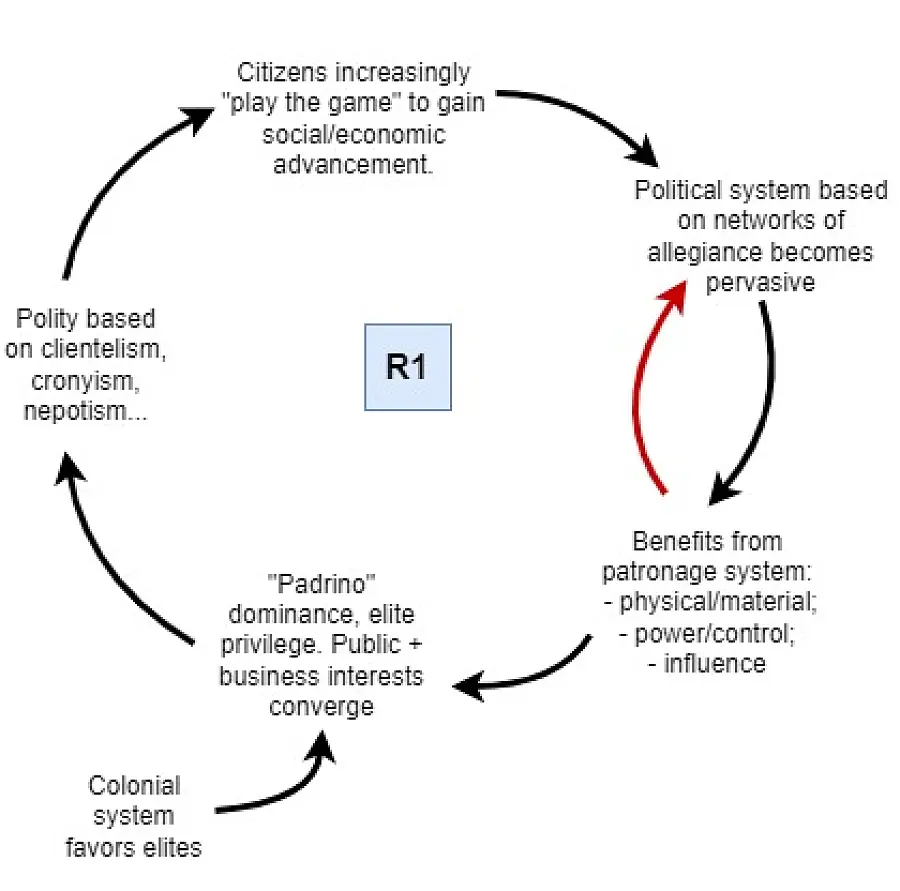

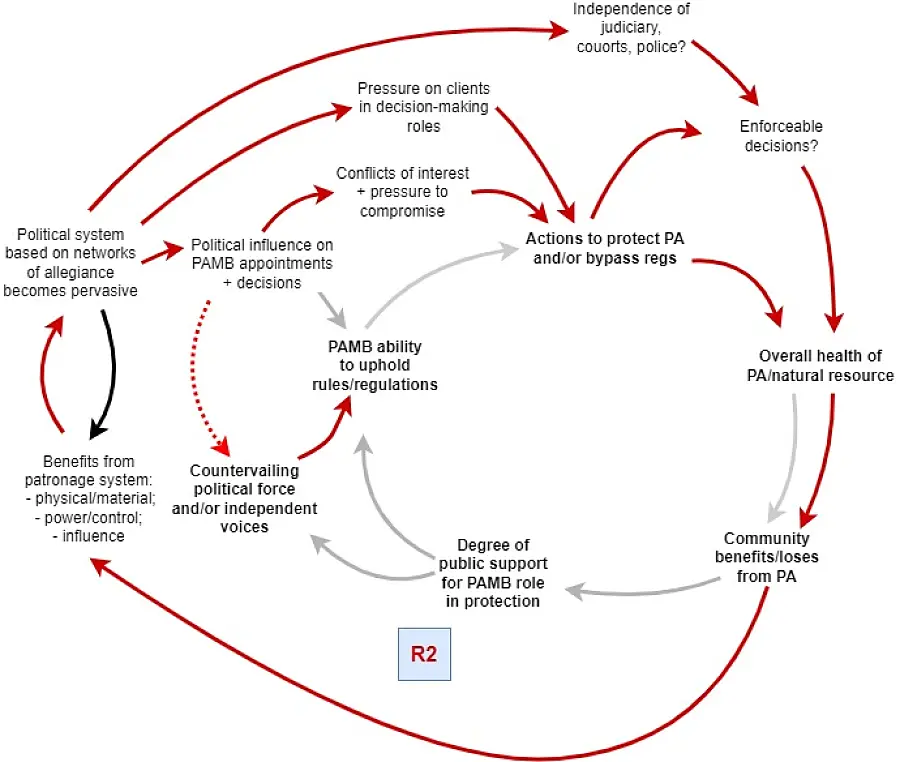

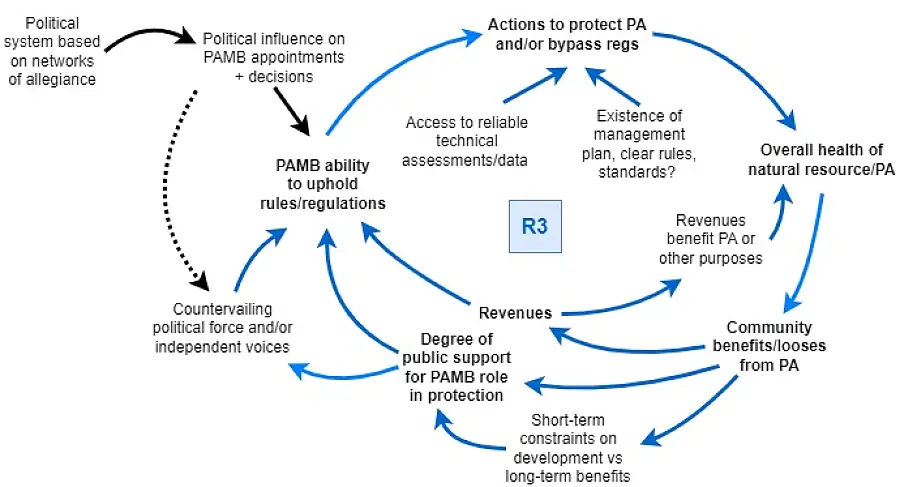

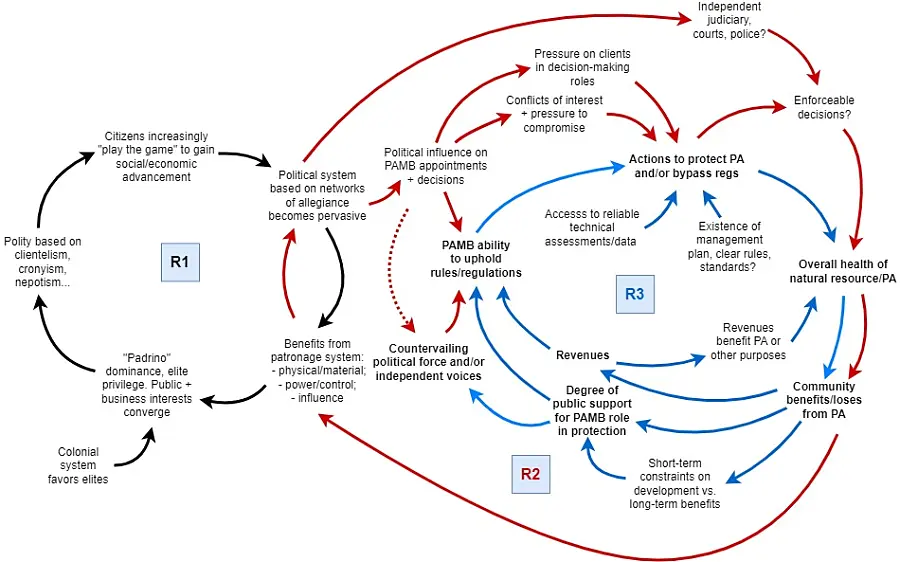

In parallel, CJL developed causal loop maps (Figures 1,2,3, and 4) that visualize the relationships between the factors involved in PAMB decision making to understand the PAMB’s operational context. Understanding the relationships between factors is useful because it facilitates the identification of strategic responses and enables one to hypothesize potential unintended negative impacts of programming (Scharbatke-Church & Barnard-Webster, 2017).

To address the second question, two international members of the research team joined the Philippines researcher to gather qualitative data at PPSRNP from September 10 to 16, 2022. The team developed a semi-structured interview protocol before travel to the site and further refined the questions once in country. The protocol was translated into Tagalog by our Philippines researcher and was tested with several Tagalog native speakers. The research team then interviewed a total of 20 people.

This methodology had some limitations that are worth noting. Due to exogenous factors such as COVID travel restrictions at the start of the research, the devastation caused by Typhoon Odette in 2021, and the uncertainty of the elections in May 2022, the research was repeatedly delayed, pushing it to the end of the funding window. Consequently, the scope of investigation was narrowed slightly to focus solely on decision-making within the PAMB. The team had to omit other areas that affect the park that might also have had corruption within them (e.g., local government offices in Puerto Princesa City).

It also became apparent as the process unfolded that the decision to focus solely on PPSRNP had limitations, given the somewhat unique governance and management structure of PPSRNP. However, there was insufficient time to compare PPSRNP to other PA sites in Palawan or elsewhere to determine the overall impact of differing governance structures on park management and corruption.

Finally, many of the meetings were set up at the request of the Protected Area Superintendent (PASU), and representatives of the PAMO accompanied the research team into interviews. These factors may have impacted the answers provided by some interviewees. However, these factors were beyond the control of the research team because the PASU/PAMO introductions were the only way the research team could gain access to key informants.

PAMB Decision Making Is Not Impacted by Regularized Corrupt Practice

The review of PAMB meeting minutes and site visit interviews with key informants revealed that, contrary to the initial macro analysis, literature review, and anecdotal discussion, PAMB decision making was not impacted by any one regularized corrupt practice. Abuse of power for personal gain was happening in the PA, but it varied in form and did not distort the decision-making process itself.

Out of 43 projects reviewed, 9 were identified as “irregular.” Although this constituted 21 percent of the projects in our sample 3-year period, the problematic cases formed a minority of investments and development activities. The projects were wide-ranging and included a basketball court, a slaughterhouse, a tourism hub, a major solar electrification project, a fishpond, roads, and the redevelopment of a large hotel.

All nine irregular projects were in violation of key national laws. With the exception of the tourism hub, the projects were either already ongoing or completed before key players applied for PAMB clearance and relevant permits/clearances (e.g., building permits, locational clearances) from other agencies. Four of these projects (the community slaughterhouse, the hotel redevelopment, and two road projects) were specifically given orders by the PAMB to stop their activities; however, all of the projects continued their activities despite the PAMB order. In all cases, the PAMB attempted to remedy the harm and damage done by these projects proceeding without appropriate clearance.

Ignoring the clearance process and violating orders from the PAMB raise corruption concerns because several of the proponents for these projects were also members of the PAMB. This, at a minimum, raises conflict-of-interest issues as well as concerns about abusing patronage systems.

For the tourism hub project, the private-sector representative on the PAMB was the owner/representative of a travel booking office. In the case of the basketball court, the local barangay captain, a member of the PAMB, was the proponent, and the project was strongly supported by another PAMB member with business interests in the barangay.* A barangay captain/chairman is the highest elected official in a barangay, which is the smallest administrative division in the Philippines. The proponent for one of the road projects was a barangay captain and member of the PAMB, while the proponent for the other road project was the city mayor. The proponent of the slaughterhouse was the barangay, represented by the barangay captain, who was also a member of the PAMB.

The proponents of these problematic projects appear to have been acting for individual reasons and exploiting the weaknesses and gaps in the governance structure in the PPSRNP. These actions can be deemed corrupt—per Transparency International’s definition—because these individuals appear to have been abusing the power entrusted to them as members of the PAMB for personal gain. Because the proponents of the projects sit on the PAMB, they should have been aware of both the formal process and the important rationale for gaining PAMB approval for commencing work. Given their position, they had more knowledge of the potential consequences (or lack thereof) and were able to take advantage of the gaps in the oversight, enforcement, and sanctions mechanisms for these self-dealing projects. They could willfully ignore the rules because they knew that doing so would not have significant consequences.

Despite the similarities between the nine cases, deeper investigation did not reveal a commonality in the specific behaviors that individuals were using to pursue their interests. The conflict of interest in each case manifested in unique ways. Further, the actions did not distort PAMB decision making itself because individual members were avoiding the PAMB process entirely. As such, our review determined that there was not a regularized corrupt practice (i.e., behavior) occurring within PAMB decision making. This was a critical finding for our research because the regularized nature of a specific behavior is an essential requirement for the existence of direct social norms.

Discussion on the Absence of Regularized Corruption

The research team was somewhat surprised to find that although there may be corruption risks and corrupt acts occurring, the PPSRNP decision-making process itself is not characterized by regular abuses of power for personal gain. This finding was particularly counterintuitive given the initial scoping discussion, literature review, and broader mapping of the sociopolitical context in the Philippines, all of which had identified corruption as a central driving theme. We provide a brief discussion of why we believe this is the case; the findings will be of interest to anticorruption and good governance practitioners more broadly.

Literature Review

The literature review conducted as part of our initial research found that corruption has long been recognized as systemic in the Philippines. Batalla (2000) and Quimpo (2007, 2009) highlight how the endemic nature of corruption in the Philippines derives from the country’s historical context going back to the Spanish colonial era and the early emergence of patron-client social relations. These longstanding historical power dynamics and patron-client relations are referred to as the padrino (Spanish for “godparent” or “patron”) system. Originally based on Catholic rituals, such as marriages and baptisms, the padrino system extends to those relationships connecting the powerful and wealthy to clients through distribution of favors and protection (Wong & Lara-de-Leon, 2018). These padrino relationships have been shown to form a chain reaching from the national to local levels, with benefits being exchanged for votes and other forms of loyalty and cooperation (Quimpo 2007, 2009).

Under the Marcos regime, political clientelism morphed into patrimonial authoritarianism, where Marcos and his cronies milked the state for personal enrichment to an unprecedented degree. Despite Marcos’ 1986 ouster and the restoration of democracy, patrimonial politics continued, enriching an expanded elite of powerful families and their friends and allies (see also Rivera, 2016).

Quimpo (2007, 2009) argues that today’s political parties, referred to as trapo (“traditional politician”), far from exemplifying weak state dynamics, are in fact strongly entrenched in and highly capable of continuing the deeply rooted elite practice of capturing state resources for personal gain. Filipino political parties do not offer coherent policies and programs; rather, their role is to act as temporary and shifting coalitions assembled to win elections (Dela Cruz, 2021) and retain power and access to resources.

Nuancing the strong-families/weak-state interpretation of Philippine politics, recent political economy analyses demonstrate how trapo parties are relatively strong, having managed to capture the state’s formal legal and institutional structures at national and subnational levels (Dela Cruz, 2021). Locally, these dynamics are referred to as “bossism,” where local politicians operate as mafia-style bosses, exercising legislative, regulatory, and economic power and distributing state-sponsored patronage. Decentralization has strengthened the authority and power of these local officials, who are the lowest-level links in the padrino chains of patronage.

Discussions with key government officials and the SIBOL team suggested that this national-level dynamic equally applied to the Puerto Princesa conservation management structure; particularly given the role of the city mayor in chairing the PAMB.

Causal Loop Mapping

The research team then undertook a process of “causal loop mapping” to understand how the social, political, economic, and conservation factors at the national level interacted with each other. The causal loop map was based on the literature review and was validated in two interviews with key informants from Puerto Princesa. Given the complex dynamics of the system involved, the map is composed of three “cycles,” each setting out a particular part of the process (cycles R1, R2 and R3). These are then combined to produce the overall causal loop map demonstrating how each of these cycles interact with each other. Figure 1 (cycle R1) presents the larger political system within which the PAMBs across the Philippines are embedded.

Patronage system in the Philippines (R1)

Source: Developed by Peter Woodrow.

The national political system operates through networks of allegiance, in which the participants gain tangible and intangible benefits, in the form of material rewards, as well as power and influence (the red/black arrows on the right of the figure). These benefits reinforce the dominance of the patronage system and elite privilege.

The system of networks of allegiance gaining benefits does not operate in isolation. It fuels political influence in the decision making of the PAMBs themselves. This analysis is represented in Figure 2.

Dynamics of political influence (R2)

Source: Developed by Peter Woodrow.

According to the available literature, the politicized atmosphere generated by the R1 patronage system (shown on the left-hand side of Figure 2 with the red/black arrows repeated from Figure 1), directly affects the way that people are appointed to a PAMB, and those people are subject to the same broader political forces at play. Before the in-country interviews, anecdotal reports suggested there might be multiple pressures that could lead to regularized corrupt decision making in a PAMB:

PAMB members may feel pressure to approve investment decisions from those they are allied with or related to, particularly if they are “clients” of more powerful patrons.

Members may have clear conflicts of interests (often business interests) that could lead them to support bypassing the regulations governing protection of the PA.

Issues may be completely local and involve curbing or yielding to the power of local business and political allies through enforcing regulations (or submitting to pressure and bypassing regulations).

Issues might involve interests at a higher (provincial, regional, national) level and even more powerful voices of support for actions that undermine the natural resource in the long term.

Even if a PAMB is able to resist pressure, members may need to consider whether a decision (imposition of a fine, blocking of a project) is enforceable, which depends on the independence of the judiciary and police or other administrative personnel, who are subject to political pressures as well. This consideration might affect how the PAMB would view the utility of reaching a decision that requires enforcement and might not be carried through.

The mapping identified that despite the laws dictating membership on a PAMB, people either holding defined government positions or representing civil society organizations do not always get appointed. This is unfortunate, because individuals in these roles can often provide a countervailing force and independent voice against undue influence. This is represented with a dotted line in Figure 2 because the appointment of such people is not guaranteed. Such countervailing forces could act as a significant bulwark against the risk of the PAMB being captured and corrupted. This overall dynamic is labeled “R2.”

Influences on PAMB membership are important because they also impact the internal dynamics of the PAMB, especially in terms of the PAMB’s ability to enforce rules and regulations. Although the PAMB oversees the management of the PA, it has no separate enforcement function. Although it is considered the highest policy-making body, the PAMB can only recommend actions to enforcers, such as the PASU and other government bodies.

Internal dynamics of the PAMB (R3)

Source: Developed by Peter Woodrow.

Building off the idea of possible countervailing forces from Figure 2 (shown in the top left corner of Figure 3 as the dotted line), the analysis identified two possible outcomes for the PAMB based on the appointment process (together shown as the R3 system in Figure 3):

Outcome 1—a virtuous circle: With sufficient countervailing forces and political support for their overall conservation activities, an empowered PAMB could decide to protect the resource, informed by reliable data and following the guidance of a management plan and clear rules and standards. That is, the PAMB could resist pressures from political and business interests. Over time, these protective decisions result in a well-managed/protected resource and a stream of community benefits that generate revenues and public support for the PAMB’s role, strengthening, in turn, the PAMB’s ability to enforce rules/regulations. There would still be tensions between people who may want to see shorter-term gains (e.g., around job creation) versus longer-term conservation goals.

Outcome 2—a vicious circle: If the countervailing forces were not able to support good governance outcomes, then decisions could be influenced by political and economic forces to bypass regulations and, over time, damage the health of the protected area. This could result in reduced benefits, lower revenues, and deteriorating public support for an empowered PAMB. Under this dynamic, short-term interests prevail over long-term protection. In addition, revenues generated by the PA/natural resource may be used to support the health of the PA or be diverted to other uses, generally with a political agenda.

Figure 4 shows the three reinforcing loops (R1, R2, R3) combined in an overall systems map of the dynamics surrounding PAMB decision making. It was clear that how this system would function could differ significantly from PA site to PA site across the country reflecting local social, economic, political, and conservation conditions.

Systems map of PAMB dynamics (R1, R2, and R3)

Source: Developed by Peter Woodrow.

PPSRNP Governance Structure

The site visit interviews revealed details of how the members of the PPSRNM PAMB were able to navigate these system dynamics to deliver positive conservation outcomes and resist corruption. This is partly due to the commitment, motivations, and work of members of the PAMB itself. However, the broader governance structure of the PPSRNP PAMB contributes to their ability to avoid the pressures present in the wider environment.

The PPSRNP enjoys a special status within the PA management system of the Philippines. The PPSRNP was first established as a national park in 1971 by virtue of a Presidential Proclamation. Following the passage of the National Integrated Protected Area Systems law in 1992, the PPSRNP moved from local city control to control by the Department of Natural Resources, which was true of all PAs in the Philippines. The same year, the Department of Natural Resources and the City Government of Puerto Princesa signed a memorandum of agreement to devolve the management of PPSRNP to the city. The city’s control over day-to-day decision making for the PPSRNP is unique in the Philippines. The research team speculates that this local control over the PPSRNP PAMB might be what insulates it from some of the broader corruption dynamics within the Philippines, although we were not able to confirm this through engagement with other sites.

Ongoing Corruption Risks

The research team did not find a single type of corrupt behavior that was regularly carried out within PAMB decision making in PPSRNP. Yet there were several potential corruption risks—representing different types of behavior—that became apparent in the course of the study. Depending on how individuals navigate the current system, the positive outcomes could also be changed into negative outcomes based on a vicious circle of political interference fueling corruption, as described in the R2 loop. In the case of PPSRNP, if the composition of the PAMB members were changed to individuals who were intent on subverting the system, a vicious cycle would be highly possible. While we did not undertake a full corruption-risk/vulnerability assessment, other risks that came up during our site visit include:

Employment conditions: The PASU holds a dual role, acting as the executive assistant to the city mayor as well as the superintendent of the PA. This creates an additional avenue for the city to politically influence the PAMB. Additionally, PAMO staff hold contract positions rather than full-time regular civil service positions referred to as plantilla positions in the Philippines. The tenuous nature of their employment creates the risk of individuals being more susceptible to external influences over fear of losing their jobs and livelihoods.

Investment approval process: There is no formal, publicly available procedure in place to obtain approval from the PAMB for projects in the PA. Not having a formal procedure makes it easier for individuals to simply ignore the process entirely and undermines the ability of the PAMB to enforce its decisions in a timely manner. It also creates the risk that projects may be commenced in good faith but cause environmental harm that cannot be appropriately mitigated. At the time of writing, a manual of operations with the recommended procedures had been drafted, but the PAMB had not yet approved it.

Absence of key guiding documents: PPSRNP has been without an updated Protected Area Management Plan (PAMP) for more than a decade at the time of writing. The absence of a PAMP has been noted as a conservation risk of “Some Concern” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature World Heritage Outlook (2020), stating that in the absence of such a plan, “effective protection and management will remain challenging.” Coupled with the lack of an approved manual of operations to clarify and control the overall process for obtaining approvals from the PAMB for investments, this increases the risk that the PAMB could engage in corrupt approvals.

Social Norms Are Not Driving the Behaviors That Are Problematic.

The review of the PAMB meeting minutes identified two problematic behaviors that have the potential for corruption and that could be driven by social norms:

Behavior one: Some elected officials advance projects in the PAs without following official procedure, even though they are PAMB members.

Behavior two: PAMB members do not regularly enforce punitive sanctions on transgressions, allowing “creative” solutions—for example, having a project proponent pay to repair some of the environmental damage caused by the building of a road—to be advanced.

Social norms influence an individual’s choice of behavior by exerting social pressure (actual or perceived) to conform to a group’s expectations. To determine whether behaviors are social norm driven, the research team explored two criteria. First, is the behavior perceived to be typical and appropriate by those who perform the acts? A typical behavior is one that occurs regularly within the same circumstances. If this criterion is met, the second criterion is whether the decision maker would face negative consequences (e.g., to their reputation or their relationships) if they made an alternative choice.

As explained earlier, although there were examples of elected officials advancing projects before gaining PAMB permission, the interviews revealed such behavior to be atypical and in general viewed as inappropriate by their peers on the PAMB. Thus, these behaviors did not meet the first criterion.

With regards to creative solutions used to resolve the negative environmental impact of projects that were advanced without PAMB approval, the creativity was a functional response to the situation. They were not driven by social pressure or expectations. Thus, the research team concluded that there was no evidence of direct social norms driving the observed behaviors.

Indirect Social Norms Do Influence PPSRNP PAMB Members

Indirect norms, unlike direct social norms, manifest in a variety of different behaviors, some positive, some negative. One can think of an indirect norm as a mutually held principle about the right thing to do. The study found indirect norms might influence PPSRNP PAMB choices but, at this time, the research team found no evidence that this influence supported potentially or actually corrupt practices.

The research team used a literature review to identify several indirect norms prevalent in the Philippines that hypothetically could drive corrupt practices. These interpretations were validated with SIBOL and PAMO staff, resulting in the exploration of whether and how six indirect norms influenced PAMB decision making:

Awa: pity for others

Malasakit: caring for others

Hiya: shame or shyness

Utang na loob: depth of gratitude

Pakikisama: unity, cohesion, harmony

Delicadeza: sense of propriety

Based on our interviews, four of the indirect norms, malasakit, awa, hiya, and utang na loob, appear to have influenced the actions of decision makers, but none were deemed to be driving problematic behavior at this time. The final two, pakikisama and delicadeza, did not have sufficient data to draw conclusions on from our interviews.

-

Awa (pity for others)/Malasakit (caring for others): Many involved in the park management process perceive these indirect norms to cause the PAMB to temper punishments or consider modifications to the rules as an act of compassion toward the poor and marginalized, especially those in Indigenous communities. While acknowledging that this happens, many of the same individuals were quick to stress that the desire to be compassionate does not override the law.

Most of the residents interviewed from within the PA had a markedly different perception. They perceived that awa and malasakit were being insufficiently honored in decisions, thereby generating a sense of resentment and negative sentiment toward PAMB members. For instance, residents viewed the PAMB as “cold hearted,” a significant slight in a Philippines context. Locally elected officials found these assertions much more personally impactful than the other PAMB representatives. This is possibly due to their long-standing relationships within the communities, the negative impact on their and their families’ reputation, and potential consequences on re-election.

The research team was unable to assess how much influence the negative assessment (i.e., the PAMB being viewed as cold hearted) had on the behavior of local officials compared with the negative political impact on a local official who is seen to not help their constituents. In other words, did local officials argue for tempering of actions because of malasakit, because they wanted to get re-elected, or for both reasons?

It is possible that these individuals may indeed be more strongly influenced by awa and malasakit in their actions. It is equally true that democracy is premised on the notion that your constituents can vote you out if they are not happy with your performance. Parsing out the mechanics of how these two dynamics—political expectations versus social group pressure—are intertwined would be an important facet to continue to explore.

Hiya (shame/shy): Hiya appears to catalyze “silence” in conversations and decisions by PAMB members who feel they do not have the same level of professional expertise as other members. Indigenous representatives were regularly named as examples of those influenced by hiya. As one member of the PAMB explained, “members do not voice their opinion during deliberations because of being shy. Also, because of being shy, they just follow/accept what others in the PAMB say.” What is not clear is whether there is an indirect social norm driving this or a simpler descriptive norm (i.e., what one perceives others in their group typically do in a particular situation).

-

Utang na loob (debt of gratitude): Interviewees were split on the prevalence of utang na loob in PAMB interactions. Some felt it did not play a role in PAMB decision making, while others indicated that “debt of gratitude” influences elected officials to align with those to whom they are politically indebted. This alignment typically takes the form of inaction. Examples included not asking questions of someone above them in the hierarchy, agreeing with positions due to “blind obedience,” or not proceeding with punitive actions when infractions are committed by those who have been political supporters.

Interviewees did not comment on their perception of whether this expectation was appropriate or what the consequences of breaching this indirect norm might be. The limited number of interviews suggested that acting against the interests of a political benefactor would be perceived as antagonistic. In that case, the actor may be seen as “an unreliable person, ingrate, or someone who cannot be trusted.” These negative social consequences for one’s reputation are not the only consequences. There are also political consequences of losing the support of the political benefactor and of their networks. Given the limited time for key informant interviews, it was difficult to determine whether utang na loob is simply a descriptive norm or a social norm among politicians and their supporters.

Conclusion

Recommendations

The study of corruption and social norms at the PPSRNP site offers a range of recommendations applicable across countries and sectors. The recommendations are intended to catalyze important questions for practitioners to consider in their work but are not to be taken as prescriptions. More research and validation would be needed before one can go to scale with formal recommendations. The conclusions are organized into two areas: (1) those specific to PPSRNP and (2) general conclusions applicable more broadly.

Recommendations Specific to PPSRNP/Philippines

-

Continue to improve good governance mechanisms of the PAMB. There were investments in the PA where individuals exploited weaknesses in the current management system to advance these projects for personal gain; however, these were not prevalent enough to be considered regularized behaviors. These weaknesses enable numerous corruption risks that continue to be present in the PAMB. To mitigate these risks:

The PAMB should work to finalize, implement, and make public the PAMP and operations manual as soon as possible.

Additional support may need to be provided to the PAMB to work with the city government of Puerto Princesa to streamline and make transparent all the processes required to obtain licenses and other approvals for investment and development activities within PPSRNP.

The PAMB should advocate to the city to make all core PAMO staff employed in official plantilla positions. This would reduce a significant corruption risk by providing increased job security.

Improving public access to PAMB decision meetings and deepening community participation in decision-making processes could also help reduce corruption risks.

-

For future projects, particularly outside of PPSRNP, carefully consider the role of indirect social norms when designing interventions. The broader contextual analysis suggests that regularized patterns of corruption occur in the management of PAs. The research team’s work in the PPRSNRP suggests that indirect social norms common to the Philippines could be central to sustaining these corrupt patterns of behavior and/or serving to block anticorruption efforts. Accounting for these indirect social norms early in the program conceptualization process could significantly enhance the results of USAID/donor/Philippines programming. This would require integrating a social norms assessment into the preliminary analysis conducted by USAID or other donors as they build their country development cooperation strategy and sector-specific program plans.

Our analysis offers some preliminary assessment of how the indirect norms we examined could be driving corrupt practices or hindering anticorruption ones, and some suggestions for programmatic responses:

Hiya (shame/shyness): It is important to take hiya into account when promoting anticorruption efforts if an element of the programming is to encourage individuals to act against those with more expertise or status. For instance, programs that promote speaking out at meetings in favor of accountability or transparency may be met with inaction by members of the Indigenous community due to hiya.

Conversely, hiya, in the context of concern for one’s personal or family honor, can prevent a person from engaging in corrupt practices to prevent bringing shame to oneself or one’s family. An anticorruption program could consider building on this positive aspect of hiya as part of a prevention effort.

Utang na loob (debt of gratitude): It is easy to imagine the possibility of taking advantage of utang na loob to engage in corrupt acts (e.g., requiring someone who has a debt of gratitude to co-sign a falsified document or to stay silent in the face of a corruption allegation). It is also likely that this indirect norm buttresses the padrino system. Understanding what behaviors utang na loob catalyzes, among whom, and the strength of the consequences of breaching the norm would be important for practitioners to understand.

Equally concerning is the role this indirect norm could have in diminishing the likelihood of people standing up to the abuse of power for personal gain. This implicit sense that one must align to those who helped them in the past, could catalyze silence and inaction when faced with problematic behaviors. This would be particularly salient to anyone working on complaint mechanisms, whistle-blower, or sanctions processes.

General Recommendations for Practitioners Working on Social Norms and Corruption

-

Work toward a common understanding of “corruption.” Given the range of definitions of and terminology around corruption, future program design, including context analysis and theory of change development, could be more effective if teams have a common understanding of what counts as corruption and why. What a donor might determine as corruption, for instance, may not align with perceptions within a local community. An analysis that specifically develops a common—locally grounded—understanding of corruption would be one way to achieve this. Some useful questions to ask as part of such an analysis would include (Scharbatke-Church & Nash, 2022):

Who is allowed to decide what is corrupt? And why (what is their role in the system and what are their motivations)?

Is there a difference between how the government defines corruption and what civil society or communities define as corruption?

What is the normative lens through which corruption is being discussed? Is the problem being framed as a criminal law problem, a social issue, or a moral issue?

Is this a “national” problem? Or are there forms of corruption specific to the place or community the project would be working on?

What impact does a “zero tolerance” approach to corruption have if local actors consider corruption to be a useful problem-solving mechanism?

Having a common understanding of corruption can help assess the applicability of anticorruption ideas generated through theory of change or strategic planning processes (see, for example, Gargule, 2021) and can avoid reverting to “cookie cutter” project interventions.

Check that perceptions align with reality of the degree of corruption. Through this process, we find that it is imperative to develop a clear understanding—based on documented evidence rather than on only anecdotes and hearsay—of the specific nature of the corruption that is undermining project outcomes. Anecdotal evidence may be insufficient proof of regularized corrupt practices, and indirect social norms can exert a powerful force in undermining good governance efforts.

-

Think of anticorruption as behavior change. Social norms drive or inhibit behaviors. “A behavior is what an individual does, such as placing a cash-filled envelope on a contract officer’s desk or demoting someone who refused to comply with a request to lose a file” (Scharbatke-Church & Nash, 2022). If we are interested in diminishing corruption, then pinpointing the specific behavior that needs to change is essential to developing an effective theory of change.

When applying a behavioral lens, it can be helpful to start with corruption typologies, as they expand the aperture beyond classic fiscal forms of corruption to include nepotism, sextortion, political interference, etc. However, that is not where specifying behaviors ends. The behavior—or regularized behavior, if one is concerned about social norms—then needs to be identified. For instance, in discussing nepotism, one would want to understand the different ways it is being practiced and by whom. Are qualified family members going through the full recruitment process and then being nudged over the finish line after a call from a superior? In this case, the corrupt behavior is the act of reaching out to pressure the hiring manager. Or is the entire recruitment process being ignored to hire unqualified family members of the recruiting manager or a powerful member of the organization? Here, the behavior is the sidestepping of the official processes within the human resources team. Responding to each of these behaviors requires different tactics. If there is evidence that these behaviors are common or regularized practices, then the response will also need to consider whether social norms are playing a role.

-

Remember silence and inaction are powerful behaviors. Most behaviors involve taking action—for example, hiding evidence to aid a politically powerful individual, changing the rules of the game, accepting cash to set a court date, or requiring a sexual act to secure a job. Yet we should not omit silence or inaction from our repertoire of ways in which abuses of power for personal gain occur. In the PPSRNP case, the research team did not find regularized corrupt practices, but the questionable incidents that were found involved some decision makers electing to remain silent—in other words, employing inaction—in the face of abuse of power for personal or political gain. This finding is supported by Scharbatke-Church et al. (2016), who found that in Uganda, inaction by civil servants is also used to exert pressure on citizens needing services (e.g., set a court date or renew a passport).

The role of inaction can also be seen in anticorruption work. Members of Kuleta Haki—a network of individuals from the criminal justice sector in Lubumbashi, DRC, known for their integrity—would commonly talk about the power of not taking action when faced with political pressure to do something that did not align with official processes. Instead, they would “wait rather than immediately acting in response to ‘orders from above’ to see if the demand [was] repeated” (Scharbatke-Church et al., 2017, p. 7). If there was no follow-up, the individual proceeded according to the rules. In effect, inaction was used as a tool to resist pressure to be corrupt (Scharbatke-Church et al., 2017).

Concluding Thoughts

The process of undertaking this study and peeling back the layers around what was occurring at PPSRNP demonstrates the importance of local, data-driven analysis to accurately identify what corrupt acts may or may not be occurring. Because of the existence of a broader system of corruption and based on the anecdotal evidence, we had expected PPSRNP to have experienced significant corruption that undermined its conservation outcomes. Relying solely on this broad national assessment and anecdotal evidence to design a program and response at PPSRNP would have proven ineffective. Going further, the research team surmises that there may be significant differences between every PAMB—even if they fall under the same national laws—that may affect whether they are also prone to corruption, what the effect of that corruption might be, and therefore what appropriate interventions might be. Thus, local, site-level analysis of corruption risks and issues is critical to be able to design and tailor effective interventions.

This research also demonstrates that that is critical to use data to test conclusions about corruption, because perceptions do not always represent reality. To develop evidence-based anticorruption approaches, it is critical to invest early in data analysis about how institutions are managed. Although corruption is often hidden, researchers can use open-source data and information to establish a more nuanced picture of what may be occurring. In this case, the open-source data were the minutes from the PAMB meetings. For practitioners working in other systemically corrupt environments, the research team encourages them to ensure they are using publicly available data to feed into their assessment and to counter what may be inaccurate narratives.

Acknowledgments

The team would like to acknowledge and thank the contributions and support from the City Government of Puerto Princesa who supported the team’s work, as well as the members of the community and Indigenous peoples in Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park whose information, views, and thoughts made this research possible. The team would also like to thank members of the Sustainable Interventions for Biodiversity, Oceans and Landscapes team including Ernie Guiang, Elmer Mercado, and Marlito Guidote for their input and support throughout the process as well as Lisa McGregor and Sarah Frazer of RTI who provided considerable guidance and constructive feedback throughout the process.

RTI Press Associate Editor: Ishu Kataria

References

To contact an author or seek permission to use copyrighted content, contact our editorial team

RTI’s mission is to improve the human condition by turning knowledge into practice. As an independent, scientific research institute, we share our findings openly - through RTI Press, other peer-reviewed publications, and media – in line with scientific standards. Sharing our evidence-based results ensures the scientific community can build on the knowledge and that our findings benefit as many people as possible.