As the world grapples with the COVID-19 crisis, RTI’s experts in public health economics are exploring ways that existing models can help efforts to plan for the post-pandemic future.

We sat down with Amanda Honeycutt and Ben Yarnoff to discuss PRISM, a predictive modeling tool designed by RTI in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Health authorities and policymakers can use PRISM to estimate what would happen in their communities if chronic disease risk factors were to change. These risk factors include management of chronic conditions, like diabetes and high blood pressure, or access to healthy foods, tobacco cessation services, or care for psychological distress.

Tell us about PRISM. What does it do, and who can use it?

Amanda Honeycutt: The Prevention Impacts Simulation Model, or PRISM, is a web-based tool that estimates the likely impact on population health of 32 chronic disease prevention and management strategies. PRISM includes strategies to address smoking, air pollution, diet, physical activity, and management of chronic conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, and psychological distress. PRISM applies evidence from the scientific literature to mathematically model the impact of changes in the strategies on disease prevalence, mortality, and costs.

PRISM is publicly available. Anyone can create an account for free and then use PRISM to examine the impact of one or more changes in the 32 chronic disease strategies. Public health and health care planners at local, state, and national levels can use PRISM to support planning for future efforts and to evaluate the impacts of past investments.

RTI worked with CDC and NIH over 15 years to develop and apply PRISM to support strategic planning for chronic disease prevention throughout the US, including in the Mississippi Delta; Austin, Texas; and several communities with Communities Putting Prevention to Work (CPPW) awards. We also used PRISM to estimate the potential long-term impacts of changes implemented by communities funded by CDC through CPPW and the Community Transformation Grants programs.

PRISM can be used to address a variety of policy questions, such as how many lives could be saved and the return on investment if 80 percent of adults with hypertension had their blood pressure under control? The Los Angeles County Health Department used PRISM to answer the question of how their CPPW grant efforts were likely to impact deaths and hospital costs over the ensuing 30 years. The Mississippi Delta and city of Austin used PRISM to answer “What evidence-based chronic disease prevention and control strategies would have the greatest impact on deaths if implemented in our communities”?

COVID-19 is a new phenomenon. How can PRISM be used to model the impact of COVID-19 in a community?

Ben Yarnoff: Although COVID-19 is not modeled directly in PRISM, the current pandemic may nonetheless affect many of the chronic disease risk factors modeled in PRISM. For example, as health care systems are stressed with the impact of testing for and treating COVID-19, they may face challenges in providing quality care for their patients with chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol. And, because recent evidence suggests that these underlying chronic conditions are associated with COVID-19 severity, understanding the impact of reduced care for these conditions could help with predictions of severe COVID-19 complications in a population. Patients with these conditions or who experience a cardiovascular disease event may also be reluctant to seek clinical care and refill prescription medicines because of fears of being exposed to the virus. Further, patients with psychological distress may struggle to obtain the care they need, especially if they lack access to virtual care providers.

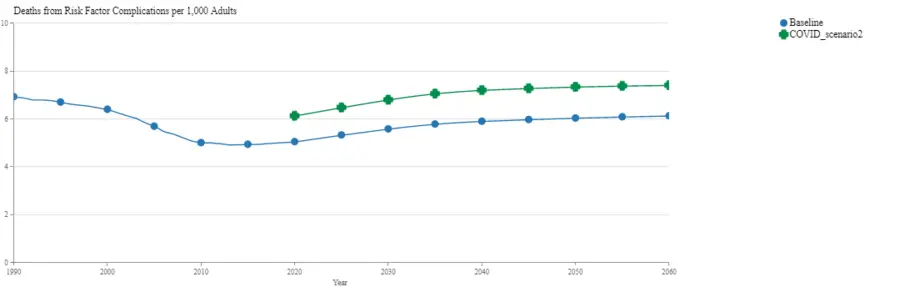

Although we typically use PRISM to explore the impact of implementing strategies to improve chronic disease management, we can also use PRISM to analyze the impacts of declines in the management and care of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors. In fact, using PRISM, we estimated that the 2020 U.S. adult death rate from these risk factors could increase from 5.0 per 1,000 adults to 6.1 per 1,000 with even modest declines in the use of quality care for diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, psychological distress, and cardiovascular disease events. That’s a 21 percent increase in deaths from these conditions – roughly equivalent to the long-term effects of doubling the number of smokers, increasing air pollution by 150 percent, and increasing adult sodium consumption by one-third.

The pandemic could also have far-reaching and long-lasting impacts on health behaviors that would affect disease and death rates for years to come. For example, smoking quit attempts are likely to decline, diet quality may be negatively affected, and physical activity may be reduced, especially for children who are unable to attend school and visit neighborhood playgrounds. The pandemic poses an immediate threat to population health that requires the expertise and ongoing support of public health agencies. But public health agencies and their partners will also be called upon to address the potential collateral damage on chronic disease management and its risk factors.

How can people in public health use PRISM to inform their decisions as the COVID-19 situation evolves?

Amanda Honeycutt: Public health and health care planners can use PRISM to explore the expected impacts of the pandemic on death rates, years of life lost, and medical and productivity costs from chronic disease and disease risk factors. They can also use PRISM to engage stakeholders, prioritize strategies to address any increases in chronic disease risk factors, and develop plans to achieve long-term objectives.

Looking ahead to future research on events like the COVID-19 pandemic, what are some key issues to consider?

Ben Yarnoff: Although the full impacts of the pandemic on health behaviors and outcomes are not yet known, previous studies have examined the impacts of disasters on population health and behaviors. For example, the World Trade Center attacks in New York City affected residents’ mental health and led to health care clinic closures that reduced patient access. Studies that have evaluated the impacts of natural disasters have found negative impacts on mental health and the nutritional quality of the affected population’s diet.

Looking forward, it’s clear that integrated approaches to address the physical and mental health needs of communities throughout the United States will be needed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic and long beyond. The health impacts and future health needs resulting from COVID-19 are likely to be broad, with potential impacts on food access and diet quality, levels of physical activity, chronic disease management, substance use and abuse, mental health, and financial stability. Successfully integrating systems and strategies to address the health needs and social drivers of health will help U.S. communities weather the COVID-19 pandemic and build resilience and capabilities to address similar challenges in the future.