COVID-19 has ground many surveys to a halt. Although COVID-19 is less prevalent in low- and middle-income countries (for now, at least), researchers have suspended face-to-face surveys to prevent the spread of the pandemic. The rapid and devastating spread of COVID-19 suggests that face-to-face surveys will not be possible for months to come. Researchers now wonder: Is it possible to collect survey data in the meantime? And how?

Surveys During COVID-19 Are Possible with Mobile

Fortunately, researchers can turn to mobile surveys during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mobile surveys are automated, inexpensive, and fast. There are three main modes to consider:

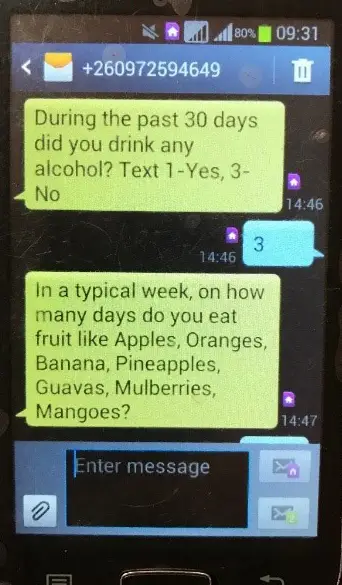

- Short message service (SMS) that use text messaging;

- Interactive voice response (IVR) or automated voice surveys;

SMS and IVR are feasible on almost every device worldwide, and rates of phone access in many low- and middle-income countries exceed 80 percent.

Another option is computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI), which uses a live interviewer. As of late March 2020, the viability of CATI during COVID-19 is unclear. Many CATI call centers have shut down already, but some vendors are setting up virtual call centers. Due to the uncertainty about CATI, we focus on SMS and IVR.

10 Tips for Researchers Considering Collecting Survey Data with SMS and IVR

Based on our project experience and methodological research on best practices for mobile surveys, here are some tips for researchers considering SMS and IVR:

- Choose your mode wisely: SMS requires literacy, whereas IVR does not. Our experiment in Nigeria shows that SMS and IVR each had similar levels of quality in terms of representativeness, but IVR is almost double the cost of SMS.

- Be concise: SMS and IVR can only accommodate 15 to 20 questions before leading to significant breakoff. If your study has more questions, consider a modular design like this one in Nepal, where a respondent completes a subset of the questionnaire in multiple settings. Or you can send subsets of a questionnaire to different sets of respondents.

- Write questions carefully: In SMS surveys, you have 160 characters for the question and response option. Steer away from “select all that apply” questions: instead, use separate yes/no questions. Always randomize the order of response options to reduce bias, our research in Kenya shows. Experiments in our projects show that subtle differences in questions (even 2-3 words in the introduction text) can impact your response rate.

- Send reminders … lots of them: Sending additional reminders is important for improving the representativeness, our research on SMS surveys in Africa shows. In our work, we generally send three reminders, each spaced 26 or 52 hours apart. For IVR studies, you can also send an SMS in advance of the IVR call attempt: this method can be effective for some studies but not all, we’ve found in South Africa.

- Incentivize your respondents: Provide a post-paid monetary incentive, usually around 1 US dollar in the form of mobile phone airtime. But 1 US dollar is sufficient: Our experiment in Kenya showed that bumping up the incentive amount doesn’t increase response rates.

- SMS and IVR work best for surveying list samples: Studies that have a list of respondents and their phone numbers can achieve high levels of representativeness, as we found in our study of vocational job training graduates in South Africa.

- Consider general population surveys, but carefully: General population surveys using random digital dial (RDD) samples generally have low response rates (1 to 10 percent, depending on the sample). They are also skewed towards male, urban, and younger populations, our research in four African countries showed. But SMS and IVR may be better than nothing. Researchers can increase the quality of general population surveys through quality survey design, well-crafted survey questions, sampling, and weighting.

- Check your sample: If you have a list sample, validate it before starting your survey. We found that creating a sample of phone numbers from old administrative records can lead to coverage bias. If you don’t have a list of participants, purchase your sample from a trusted vendor. When you’re collecting data, remember to confirm who you’re speaking with, as many people share phones with other people.

- Mix modes to improve quality: Starting in one mode, then following up with non-respondents in a different mode can improve quality, according to a study we conducted in South Africa. Looking for a mixed mode tool? With the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and InSTEDD, RTI developed Surveda, a free, open source tool that fully integrates SMS, IVR, and Web mixed mode surveys.

- Run a pilot first: For those unsure about whether mobile is a good fit, run a pilot study to assess the feasibility of these modes for your project. Consider running virtual or phone-based cognitive interviews to ensure questions are valid and reliable.

Getting Started with Mobile Survey Data Collection

Taking the above tips into account, consider adopting SMS or IVR. Switching survey modes on short notice may understandably be a little uncomfortable for many researchers at first. But crisis oftentimes sparks innovation. And for some projects, these modes may be the only way to collect data in the months ahead. Feel free to contact the author if you have any questions. Also, please see the "Further Reading" section at the end of this page for an extensive list of recommended articles.