This blog post is adapted from our June 10 response to the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) request for information (RFI) 2019-08818: Developing a Federal AI Standards Engagement Plan. This RFI was released in response to an Executive Order directing NIST to create a plan for the development of a set of standards for the acceptable use of AI technologies. Given the wide adoption of AI technologies and the lag in commensurate laws and regulations, this post aims to help NIST by highlighting the current state, plans, challenges, and opportunities in ethics and AI.

Data Protection Regulations Around the World: An Opportunity to Lead by Example

In 2016 the European Union (EU) created the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that would expand protections around EU citizens’ personal data beginning in 2018. Meanwhile, China has extensively integrated AI technologies into their government and social structure via the China Social Credit System. Under this system, the Chinese government employs widespread data collection and analytics to monitor the lives of its citizens. Citizens get scored based on everyday decisions like what they purchase and what they do in their free time, and their scores are affected by the scores of their family and friends. An individual’s score amounts to a social ranking, and it impacts a variety of aspects of one’s life, like the ability to travel throughout the country, acquire loans and receive an education. The Chinese Social Credit System is at odds with U.S. perspectives on the values of liberty and freedom as well as other countries’ values on personal data privacy and protection as seen with the GDPR. As China continues to heavily integrate AI into daily life, the country is setting an international precedent for what it considers ethical AI.

The U.S., in collaboration with other nations, has the opportunity to be a leader in defining ethical and responsible practices around AI and AI-related technologies. The growing ubiquity of data collection continues to enhance the power of predictive analytics and AI to an extent that most U.S. laws and regulations have not accounted for. The federal government has nonetheless made steps towards being in an informed position for regulating AI. For example:

- 2016 formation of the National Science and Technology Council Subcommittee on Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence, to help coordinate federal activity in AI and create the National Artificial Intelligence Research and Development Strategic Plan

- Introduction of the FUTURE of Artificial Intelligence Act of 2017.

- 2019 launch of AI.gov, which features AI initiatives from the administration and federal agencies

Local governments are beginning to create regulations on their own, as seen with San Francisco’s May 2019 voting to ban the use of face-detection software by city agencies and law enforcement. Nevertheless, most regulation around AI currently depends on those who are creating the AI technologies. This can be problematic, since these creators may have incentives that conflict with the privacy or long-term interest of their users, as well as non-users who are affected by the use of AI technologies. In these situations, the U.S. government may have an opportunity to expand AI regulation that protects citizens’ interests.

Ethical Issues Related to AI

The ethical issues facing AI have a wide scope. These issues include data collection, storage and distribution as well as machine or statistical use of data and how a subsequent AI product interacts with the world. AI systems face problems of bias through a variety of channels such as the underlying societal systems that affect a sample’s population, design decisions made by an AI engineer or an AI system’s actual implementation in the real world. Biased AI technologies can reinforce existing biases in society and can harm individuals in select communities. There are many stakeholders in ethical AI, including but not limited to individuals, governments, countries, ethnic groups, cultures and corporations.

Given the human-specific nature of most AI technologies, the ethical frameworks that have emerged out of medical and biological research are good reference points for ethical evaluation of AI. In particular, there are a few key concepts that could extend to ethics in AI:

- Autonomy – Being “free from both controlling interference by others and from limitations, such as inadequate understanding, that prevent meaningful choice.”

- Informed Consent – One providing permission for or agreeing to an activity in which one is involved or directly affected by (e.g., a medical procedure). A threshold for informed consent is not always clear, but it typically requires that one who provides consent has sufficient information about the activity to which one is consenting. Additionally, it requires that one has the capacity and maturity for understanding the decision they are making (e.g., they are not a child). Finally, the individual must also be free from outside influence, like coercion, in their decision making.

- Coercion – Compelling one to act against one’s will by threatening violence, reprisal, or other intimidated behavior that puts one in fear of the consequences of not complying.

- Undue inducement – Influencing one’s decision or action by offering one an incentive that is so large or enticing that it undermines one’s ability to rationally consider the costs and benefits of such a decision or action.

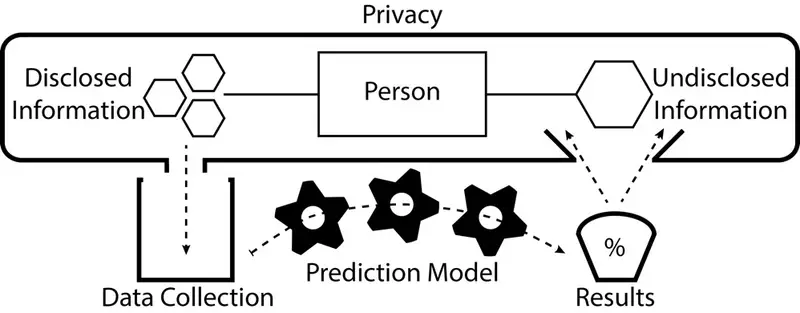

Most individuals interact with AI technologies created by corporations, and corporations define the rules for using their technologies via Terms of Service agreements. Many issues can begin to emerge when evaluating these agreements under the ethical concepts listed above. For example, companies often retain the right to change their Terms of Service agreements, so a user may agree to certain data retention conditions but then find that the originally agreed upon terms are no longer the active terms of use. Depending on the situation, the company may not provide clear communication about the change and the user could have false expectations. In situations where companies are using an individual’s data in research or to predict something about them, this could be problematic under the lens of expectations in informed consent. As shown in Figure 1, an individual may knowingly disclose certain personal pieces of information, but they may do so without knowing that the disclosed information will be used to predict something undisclosed.

Figure 1: Illustration of disclosed information being used to predict undisclosed information.

For example, the retail store Target developed a pregnancy prediction model to predict if their shoppers were pregnant based on their purchasing history. At the time, it was unlikely that the general consumer had an expectation that their purchasing behavior was being used to predict whether or not they were pregnant. Additionally, there was a secondary problem of “domain transference” since Target inferred medical outcomes for customers using non-medical data and acted on the predicted outcomes by sending targeted advertisements.

Medical information is typically protected under regulation of Personally Identifiable Information (PII) data. Yet, the growing sophistication and adoption of AI technologies is making it easier to extrapolate undisclosed medical or psychological information using out-of-domain data like social media behavior. Understanding how AI technologies work requires a deep level of education and experience with statistics and AI implementation. Given the complexity of AI and the requirements of informed consent, it is questionable whether an average citizen could consent in an informed way to data collection that will involve future AI research, especially if that research is not clearly defined.

Some leaders at the technical end of AI have more formally defined guiding ethical practices. For example, Google has outlined principles for developing AI responsibly:

- Be socially beneficial

- Avoid creating or reinforcing unfair bias

- Be built and tested for safety

- Be accountable to people

- Incorporate privacy design principles

- Uphold high standards of scientific excellence

- Be made available for uses that accord with these principles

Companies like Google face inherent limitations in their ability to self-monitor ethical issues. This was seen when Google canceled its AI Ethics Board less than two weeks after its launch due to internal and external criticisms of board member conflicts of interest.

With the growing availability of AI-powered autonomous and semi-autonomous vehicles, there are underlying concerns in how machines will react in situations that require decision-making that could affect pedestrian or passenger lives. Additionally, when accidents occur that involve autonomous vehicles, questions around culpability arise, which could involve pedestrians, passengers, vehicle companies and their leaders, AI software companies and their leaders, and AI engineers.

U.S. Laws & Regulations Relevant to AI

When making any ethical evaluation of AI one must also acknowledge relevant laws, regulations, community values and corporate policies. Moreover, law embodies ethical values, and in order for the U.S. to establish an ethical position in AI it must have its position reflected in laws and regulations. With AI being driven primarily by academia and corporations, there are few U.S. laws and regulations specifically aimed at AI and data in its modern context. That said, there are well-established laws and regulations that provide guidance for dealing with privacy and citizen rights that extend to the recent data-driven software technologies.

At the U.S. federal level, a keystone for guidance and philosophical perspective is the Fourth Amendment:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

In Katz v. United States (1976), the U.S. Supreme court established an extension of the Fourth Amendment called the Reasonable Expectation of Privacy Test. The test consists of two requirements:

- An individual has exhibited an actual (subjective) expectation of privacy

- The expectation is one that society is prepared to recognize as reasonable

Under this test, if these two requirements have been met and the government has taken an action that violates the expectation in question, then the government's action has violated the individual's rights under the Fourth Amendment.

Later, in United States v. Miller (1976) and Smith v. Maryland (1979), the courts established what is known as the Third-Party Doctrine, which holds that information one voluntarily gives to a third party does not carry a reasonable expectation of privacy (e.g., bank records, dialed phone numbers). However, in Carpenter v. U.S. (2018), the Supreme Court found that the Third-Party Doctrine did not apply to cell phone location data.

Specific laws that define the extent of an individual’s right to privacy from other individuals can vary by state, county and city. For example, taking photos while on a public space (e.g., a sidewalk) is typically unrestricted even if the photos are of a private space (e.g., a person’s yard) – with exceptions of private spaces like bathrooms and bedrooms – but a property owner can bar one from taking photos while on their property. Additionally, recording audio of individuals can face certain restrictions, such as requiring consent from various parties who are being recorded.

The Future of AI Regulations

The U.S. has an opportunity to lead the way in defining guidelines, regulations and laws that address ethical issues in AI. With differing perspectives on what constitutes ethical AI across nations, it is important that the U.S. clearly defines its position in such a way that is consistent with the values defined in the U.S. constitution and body of law. The ethical frameworks developed in medical and biological research are good reference points for ethical evaluation in AI, given the human-focused nature of many AI systems. In particular, notions of informed consent may need to be more thoroughly evaluated when considering data collected on individuals and the variety of predictive information that can be garnered from that data. While the U.S.’s legal position on AI and associated practices and technologies is nascent, there are well-established legal precedents that can serve as a backbone for more specific AI regulations and law.