The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a historic spike in unemployment insurance claims, and there is growing consensus that the economy is headed for a potentially deep and protracted recession. In the past, postsecondary credentials or degrees have helped mitigate the impact of an economic downturn. Of all new jobs created after the Great Recession, 99% went to individuals with some type of postsecondary training. Not only can postsecondary education help in times of economic distress, but at least some college education is becoming ever more necessary for earning a living wage in the 21st-century economy.

Unfortunately, not all groups have the same levels of postsecondary education enrollment and attainment, with particular challenges for low-income populations and people of color. The growing need for postsecondary education coupled with continued, unequal access is a recipe for a widening gap between the haves and the have-nots—a gap that will likely be exacerbated by the current pandemic.

Policy responses to this persistent inequality have generally sought to address individual barriers to college access, whether financial, academic, cultural, or logistical. Since 2006, we have been studying a model—early college—that takes an entirely different approach. Early colleges ask a conceptually simple question: If we want more people to have postsecondary education, why don’t we just combine high school and college together?

What are early colleges?

Early colleges are small schools that seek to seamlessly integrate high school and college. Frequently located on college campuses, they enroll students starting in 9th grade and provide them with early access to the college experience. Students remain in these schools for four or five years, during which time they complete their high school diploma and earn an associate degree or two years of transferable college credit.

Despite offering rigorous academic coursework, early colleges are not focused on gifted students; instead they target students who might traditionally face challenges in making the transition to college, such as low-income students, students who are the first in their family to go to college, and students who are members of racial and ethnic groups underrepresented in college. To minimize barriers that these students may face, early colleges also provide extensive academic and affective supports. The early-college model is being implemented broadly across the country, with more than 100 schools in North Carolina, over 170 in Texas, over 100 in Michigan, and more in many other states.

Do early colleges work?

We have been conducting a 14-year rigorous experimental study of North Carolina’s early-college model. Our study, which has been determined to meet federal standards for a high-quality research design, compared results for students who applied to early colleges and were accepted through a lottery (our treatment group) to students who applied but were turned down through the lottery (our control group). This research design ensures that we are comparing apples to apples.

We found 27% of students in our treatment group graduated from high school with an associate degree or technical credential, compared to 2% of our control group. An additional 47% graduated with at least some college credit, compared to 26% of the control group. Even if early-college students do not go on to any further education, they are much more likely to enter the workforce with some postsecondary training.

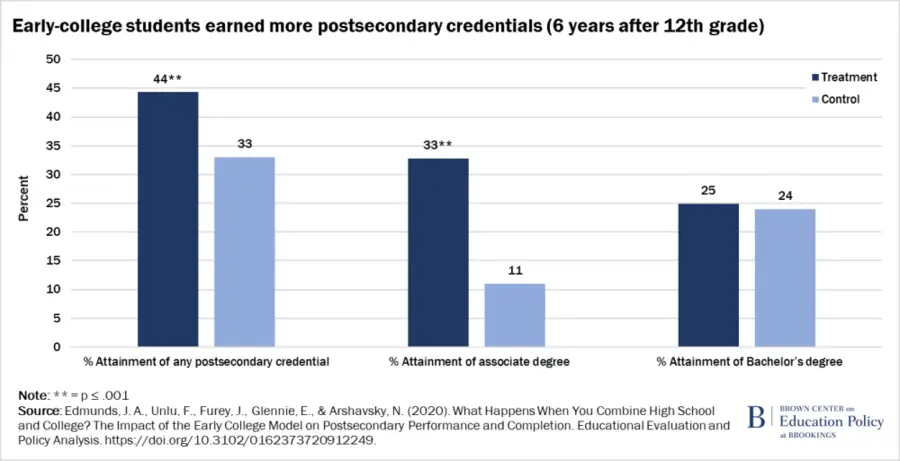

Many do pursue further education, though. Our most recent published findings looked at credential attainment by six years after 12th grade. We found that:

- More early-college students earned postsecondary credentials than control students. More than 44% of treatment students had earned some sort of postsecondary credential by six years after 12th grade, compared with 33% of the control group.

- Early-college students were three times as likely to get associate degrees as control students. 33% of early-college students earned an associate degree, compared to 11% of control students.

- Despite the higher rate of associate degree attainments, early-college students were not being steered away from bachelor’s degrees. Our research indicates no differences in the attainment of bachelor’s degrees between treatment and control students in the full sample. In fact, there was a 4.5-percentage-point positive impact on bachelor’s degree attainment for economically disadvantaged students.

- Early-college students earned their degrees more rapidly. The early-college model shortened students’ time to degree by two years for associate degrees and by six months for bachelor’s degrees.

- Despite spending less time in college, early-college students did equally well academically. Both groups had essentially the same average postsecondary GPA.

In addition to these impacts on postsecondary degree attainment, our prior research in North Carolina has shown that early-college students were more likely to complete high school courses required for college; students also had higher attendance and lower suspensions. Early-college students reported better experiences in school than control students. They were also more likely to enroll in college.

Finally, we’ve taken a preliminary look at the costs of the early-college model. While we found that early colleges were more expensive than a traditional comprehensive high school, they were a less expensive route to a two-year degree and a much less expensive pathway to earning a four-year degree.

What do these results mean?

The early-college model demonstrates that combining portions of high school and college is possible. Our results to date show many advantages, including an increase in degree attainment and less time to degree, which should benefit the students who attend these schools as well as society more broadly.

Some might argue that students will miss out on important learning if they earn a high school diploma and a two-year degree at the same time. At this point, we do not have any evidence to support that argument. Instead, we have found that early-college students perform just as well as students in the control group when they enter further postsecondary education. It is possible, as the president of Stanford argued 100 years ago, that the separate evolution of our secondary and postsecondary systems have led to unnecessary redundancies between the two.

We do not yet know how long or deep this economic downturn will be, or how the pandemic will affect the way we work and learn. However, if past patterns hold, having some postsecondary training will be more important than ever. And just as the post-coronavirus workplace is surely being re-envisioned, this crisis should motivate us to reconsider the structure of our educational system. Early college is a model that can help inform these discussions.