This blog was originally published by the Health Affairs Forefront on November 15, 2022.

Individuals dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid have a high prevalence of chronic conditions and functional limitations, as well as high health care and long-term services and supports (LTSS) use and expenditures. Sixty percent of dually eligible individuals have multiple chronic conditions, and 49 percent receive LTSS. Dually eligible beneficiaries represent only 15 percent of Medicaid enrollment, but more than one-third of Medicaid expenditures.

Over the past decade, enrollment among dually eligible individuals in models that integrate the delivery and financing of care across Medicare and Medicaid has increased almost tenfold. Integrated care is intended to align the delivery, payment, and administration of both programs’ services, with the goals of improving care, eliminating incentives for cost shifting, and reducing spending that may arise from duplication of services or poor care coordination. Care coordinators or teams, often part of integrated care models, create person-centered care plans and work to coordinate care across service providers. In Medicare Advantage (MA), integrated care is a central component of certain plan types (exhibit 1), including (but not limited to) Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs) and Fully Integrated Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (FIDE-SNPs). Other models of integrated care include Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) and Medicare-Medicaid Plans (MMPs) under the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS’s) Financial Alignment Initiative (FAI) demonstrations with states.

Exhibit 1: Types of integrated care models

As the landscape of integrated care models continues to evolve, it begs the question—do these integrated care models deliver better outcomes compared to non-integrated MA plans?

Research Assessing The Effects Of Integrated Care Models Is Limited

Based on a review of studies published between 2004 and 2020, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) reported mixed findings regarding the effectiveness of integrated care models. Study findings generally aligned for certain outcomes (for example, fewer hospitalizations and readmissions for dually eligible beneficiaries in integrated care models, compared to those in non-integrated models) but were mixed for others (for example, emergency department use, LTSS use, and beneficiary experience). In general, studies lacked generalizability because they only focused on one type of integrated care model, included limited geographies and populations, and were limited to specific time frames. Due to these limitations, it is hard to determine the effectiveness of both individual integrated care models and integrated care broadly because models can vary significantly in their specific care delivery approaches, geographic distribution, frailty of the population they serve, and the extent of service integration. PACE, for example, includes an interdisciplinary team and site-based services at an adult day center. In contrast, most D-SNPs do not include single care teams, and beneficiaries receive care at the site of their community providers, as they would in a typical managed care plan.

Until recently, research comparing outcomes for dually eligible individuals in integrated care models has been hindered by the lack of timely, accurate service utilization data submitted by the managed care plans, known as encounter data. But in 2019, CMS released MA encounter data for 2015, the first year such data were deemed sufficiently complete and useable for research purposes. Using these data, RTI International and the Office for the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation conducted exploratory analyses to determine the feasibility of evaluating outcomes across multiple types of integrated care models nationally—the first endeavor of its kind, to our knowledge.

Integrated Care Models Are Associated With Favorable Outcomes For Dually Eligible Individuals

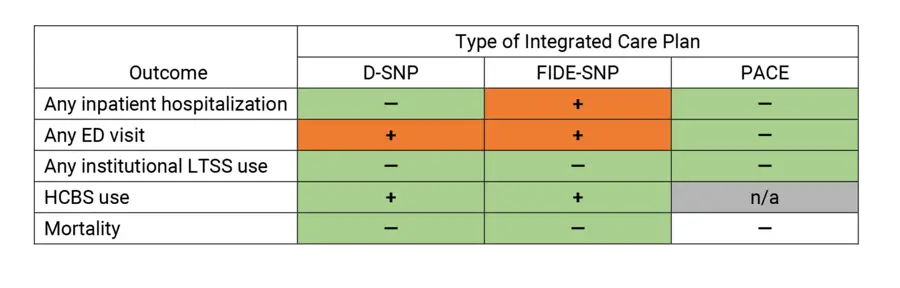

We compared five service utilization and outcome measures (any inpatient hospitalization, any emergency department [ED] visit, any institutional LTSS use, any home and community-based services [HCBS] use, and mortality) among dually eligible individuals enrolled in three types of integrated care models—D-SNPs, FIDE-SNPs, and PACE—each relative to dually eligible individuals enrolled in regular, non-integrated MA plans. For each measure, we conducted a multivariate regression analysis that controlled for beneficiary demographic characteristics, comorbidities (as measured by nearly 80 Hierarchical Condition Categories [HCCs]), and an indicator for each state to account for variations in state policies and other state-specific factors that were not measured but could influence the outcome. Our analysis excluded beneficiaries enrolled in MMPs because they are being evaluated as part of the FAI demonstrations.

After adjusting for beneficiary demographics and comorbidities, we found promising evidence that dually eligible individuals enrolled in these integrated care models had, in general, a more favorable pattern of service use and mortality than those in regular, non-integrated MA plans. Compared to dually eligible individuals in regular MA plans, our findings indicate that those in D-SNPs and PACE had lower odds of hospitalization, while beneficiaries in FIDE-SNPs had higher odds of hospitalization (see exhibit 2 for a visual summary). Dually eligible beneficiaries in D-SNPs and FIDE-SNPs were more likely to visit the ED than those in regular MA, while those in PACE were less likely to do so. Furthermore, dually eligible individuals in D-SNPs, FIDE-SNPs, and PACE were less likely to use institutional LTSS, and those in D-SNPs and FIDE-SNPs were more likely to use HCBS, than those in regular MA. Additionally, we found that dually eligible individuals in D-SNPs and FIDE-SNPs had significantly lower mortality risk than those in regular MA plans, while the mortality risk of those in PACE did not differ significantly compared to those in regular MA plans, despite higher average frailty levels.

Exhibit 2: Multivariate regression associations between integrated care plan enrollment and service use and mortality among dually eligible beneficiaries in 2015, compared to enrollment in a regular MA plan

Source: Authors’ analysis. Notes: D-SNP is Dual Eligible Special Needs Plan. FIDE-SNP is Fully Integrated Dual Eligible Special Needs Plan. MA is Medicare Advantage. LTSS is Long-term services and supports. PACE is Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly.

— Indicates lower odds of an outcome associated with an integrated plan type, compared to regular Medicare Advantage (MA).

+ Indicates higher odds of an outcome associated with an integrated plan type, compared to regular MA.

Integrated Care Models Hold Promise But More Research Is Needed To Assess Their Operations And Performance

Our findings show that full-benefit dually eligible beneficiaries in D-SNPs, FIDE-SNPs, and PACE were less likely to be institutionalized than those in non-integrated MA plans. Furthermore, enrollment in D-SNPs and FIDE-SNPs was associated with a greater likelihood of using HCBS, an area of service use that had not been included in many prior studies of integrated care models. However, enrollment in some plan types was also associated with higher rates of ED visits and hospitalizations.

PACE, known for its focus on HCBS provision and full integration of a range of medical services and LTSS, stands out in our analysis as a consistent high performer. Findings suggest that PACE may be successful in not only reducing institutionalization but also reducing hospital use. However, although present in 30 states, total PACE enrollment is merely 55,000 participants nationwide, a tiny portion of all community-living older adults with nursing-home level-of-care needs. Among other factors, high upfront capital investment and operating costs are likely constraints on further expansion of the PACE program.

The Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) of 2018 and subsequent CMS rulemaking included additional requirements related to D-SNP integration of LTSS and behavioral health services beginning in contract year 2021. These new requirements have the potential to transform the integration landscape. As more plans gain FIDE-SNP status, and as increasing numbers of plans meaningfully integrate behavioral health services, new policy questions emerge. Will the outcomes for FIDE-SNP enrollees change as enrollment increases? What happens when beneficiaries go from enrollment in a D-SNP to a FIDE-SNP with a presumably higher degree of integration? How well do these integrated care models serve beneficiaries with behavioral health needs? And importantly—as the availability of integrated care increases, are there social or environmental factors that influence access to care?

Given the recent public release of the encounter data and the scarcity of published work using these data, additional research using more recent years of encounter data is needed to validate our findings and inform ongoing and future policy discussions in this area. Future research should use more rigorous methodological approaches, including conceptual frameworks and hypotheses and methodologies that mitigate beneficiary selection bias, as suggested by the considerable differences in the demographic and health-related characteristics of the dually eligible beneficiaries enrolled in different plan types. It also should focus on evaluating new or often overlooked service use and outcome measures (for example, Medicaid spending) and outcomes by subgroups of dually eligible individuals, as well as comparing effectiveness among different types of integrated care models.

Additionally, future work should address the following limitations of our analyses. We included all full-benefit dually eligible individuals enrolled in D-SNPs, FIDE-SNPs, PACE, or regular MA plans who met study inclusion criteria. While using this study population is reasonable for an exploratory analysis, future research could be enhanced by creating a matched comparison group of dually eligible individuals in non-integrated MA plans with characteristics and risk profiles similar to their counterparts in integrated models. This could take into account the fact that integrated plans are more concentrated in some geographic areas than others. Our results also do not inform comparisons of MA plans with traditional Medicare, although recent research found dually eligible individuals with traditional Medicare reported less access to care, lower preventive services use, and lower satisfaction with care than those in D-SNPs.

CMS and many states have prioritized improving care and reducing costs of care for dually eligible beneficiaries by supporting integrated care models. With the advent of increasingly reliable and useable nationwide MA encounter data, researchers and policy makers can now begin to leverage these data to address important policy questions surrounding the coordination and integration of care for the dually eligible population.

Authors’ Note

The authors’ analysis as described in this article was based on a project conceived and funded by the Office for the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation and conducted by RTI International.