A Toolkit for Researchers and Practitioners

Patient-centered communication (PCC) helps provide high quality, patient-focused medical care. This toolkit, Advancing Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: A Toolkit for Researchers and Practitioners, offers practical approaches to measuring PCC for purposes of quality assessment and improvement, monitoring and surveillance, and research. The toolkit is intended for researchers, evaluators, and professionals who play a role in assessment and quality improvement in cancer care (e.g., quality improvement, training, and clinical leadership).

Patient-centered communication (PCC) helps provide high-quality, patient-focused medical care. Although PCC has been conceptualized in multiple ways, most agree that clinicians communicating in a patient-centered way

- show care and respect for the patient as a person;

- solicit the patient’s perspective and preferences;

- try to understand how the patient’s health is affecting their everyday life and well-being;

- involve patients in their care; and

- make evidence-based decisions that are consistent with patient values and feasible to implement.

Achieving PCC in diverse cancer care settings depends on

- the extent to which important elements of PCC can be measured and assessed; and

- researchers’ and clinicians’ efforts to identify the “pathways” through which accomplishing PCC in medical encounters can improve patient outcomes, such as

- patient satisfaction with care,

- commitment to treatment plans, and

- improved health and well-being (biomedical, psychological, and quality of life).

Figure 1. Patient-Centered Care

Clinicians, patients, relationships (clinical and social), and health services are all integral to patient-centered care. The interactions among these elements are complex and deficits in any one area can significantly decrease the quality of patient care.

The approach to PCC described here is based on the National Cancer Institute’s 6 function model of PCC in cancer care. Rather than assessing a clinician’s communication style with patients—such as friendly, informative or supportive— the model focuses on the work that communication must do well to achieve PCC.

The 6 key functions of PCC include:

- Information exchange

- Fostering healing relationships

- Managing uncertainty

- Making decisions

- Managing emotions

- Enabling self-management.

These 6 functions are not independent of one another. For example, information exchange is a critical part of effective decision-making and can help cancer patients manage emotions, which helps foster healing relationships. Although these functions are interconnected, they also relate to distinct communication domains requiring effective clinician-patient communication to achieve high-quality cancer care.

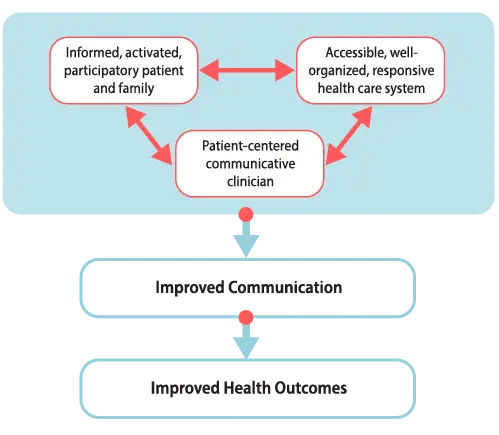

Figure 2. Patient-Care Communication Model

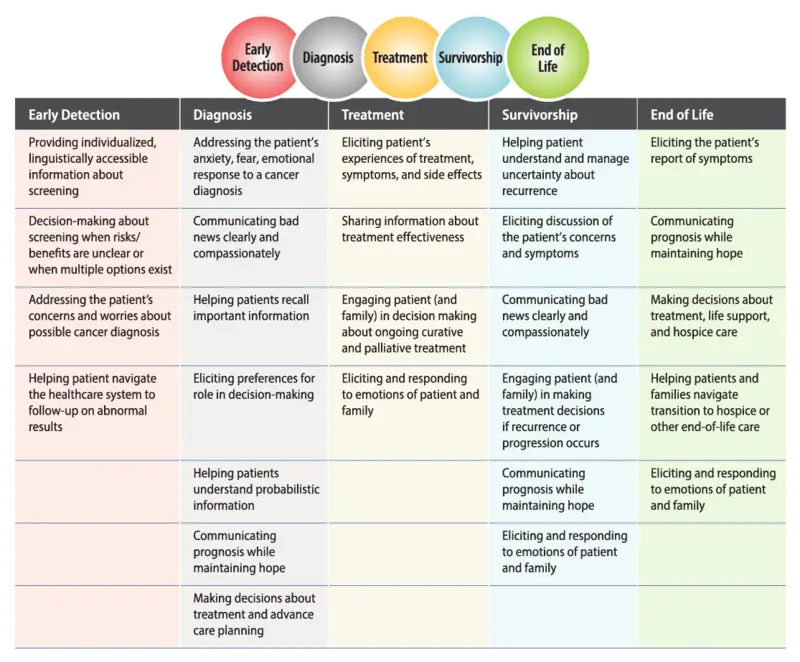

One way to understand the utility of the NCI model of PCC is to show how the different communication functions apply to different stages in the cancer control continuum.

For example, prevention and screening rely heavily on communication focused on information exchange, especially as it applies to an individual’s understanding of cancer risks, behaviors that minimize risk, and the importance of routine screening for early detection.

Diagnosis, including sharing bad news, requires clinician communication that help a patient manage difficult emotions and fosters healing relationships so that the patient and their family understand they are supported, cared for, and will not be abandoned.

During the treatment stage, a patient may have options for how to treat their cancer. Consequently, effective decision-making is essential as the clinician and patient work together to create a treatment plan supported by the evidence and consistent with the patient’s preferences and values. During treatment, enabling patient self-management is also critically important because a patient and their loved ones need to know how to manage side effects of the disease and treatment—such as pain, fatigue, and nausea—as the patient returns to everyday activities outside the clinic.

During the survivorship stage, managing uncertainty is especially important because the patient may wait, often for weeks and months, to see if treatment leads to cure or remission; and, if so, whether there will be a recurrence. This is not to say that within each stage the other communication functions are less important. As mentioned above, all of the functions are interconnected in practice, but communicating successfully in certain domains will be particularly important.

Patient and Caregiver Perspectives on Cancer Care Communication

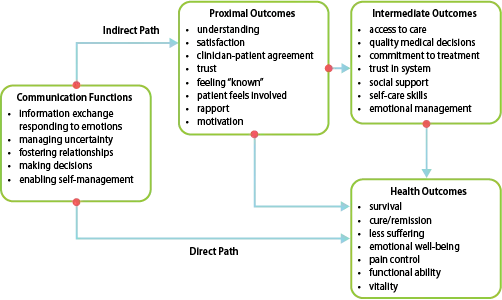

Conventional wisdom holds that PCC is important in cancer care and contributes to higher quality of care and improved health outcomes. But in what way and based on what evidence? To answer these questions, it is helpful to use a model that describes the potential “pathways” through which PCC can lead to better cancer care and improvement among multiple cancer care outcomes, such as pain control, psychological well-being, remission, and improved physical function.1 (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Direct and Indirect Pathways from Communication to Health Outcomes

Although clinician-patient communication can directly affect health outcomes, more often than not effective communication will have an indirect effect on health outcomes via its effect on factors closely linked to better health and well-being:

- Greater patient satisfaction with the support and information received from the healthcare providers

- Stronger patient commitment to the treatment plan

- Better self-care and caregiving skills for managing symptoms and side effects of treatment

- Coping with difficult feelings

Consider some examples from investigations that identified pathways through which PCC contributed to better cancer care and outcomes.

Physicians who more actively involved cancer patients in the decision-making process (decision-making) had patients who reported more confidence in managing the disease and had a greater sense of personal control, which in turn predicted better emotional well-being.2

In a study3 of patients with advanced cancer who were having problems with pain, patients who openly expressed their problems with pain and preferences for pain management (information exchange) were more likely to have their physicians make adjustments in their pain medications. Patients receiving a change in pain management were more likely to report better pain control several weeks after the consultation than patients staying on the same regimen.

An investigation that analyzed videotapes of surgeons’ consultations with breast cancer patients4 reported that patients’ expressed greater satisfaction with their care when they were more engaged in stating treatment preferences (decision-making) and when their surgeons provided more good and hopeful news (information exchange, managing emotions). Greater patient satisfaction, in turn, predicted more hopefulness about their treatment following the consultation.

In a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy,5 patients who reported being more engaged in seeking and sharing information (information exchange) and patients that perceived better relational communication with their doctors (fostering healing relationships) reported better coping and less anxiety, which then predicted higher quality of life.

In short, PCC matters. To use a journey analogy, PCC is the key that starts care moving down the road to better cancer care and well-being.

Patients’ and family members’ experiences of cancer and cancer care are highly influenced by how their providers communicate with them. Patients value sensitive, caring clinicians who

- provide information that they need, when they need it, in a way that they can understand;

- listen and respond to their questions and concerns; and

- make an effort to understand what the patient experiences.6

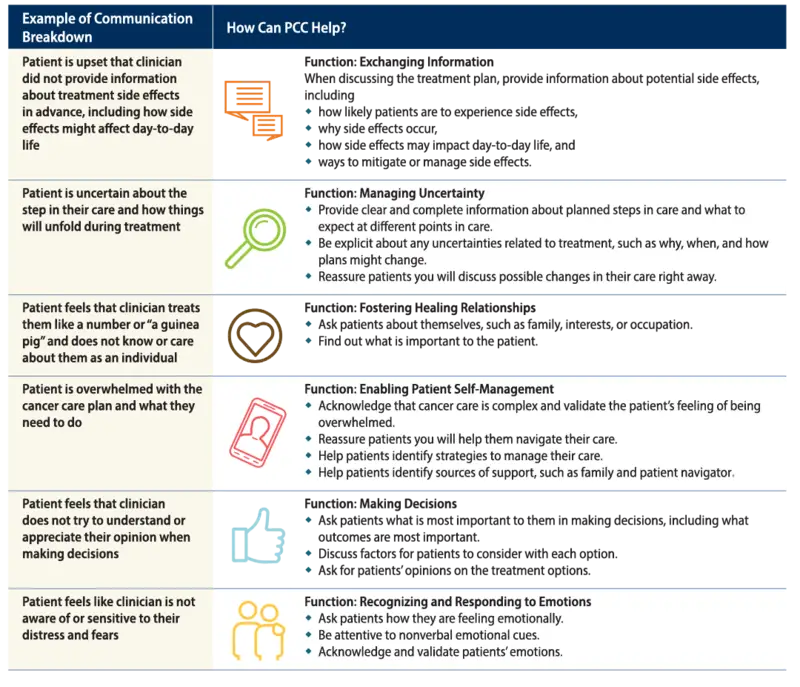

Communication Breakdowns and the Role of PCC

Potential Communication Breakdowns and the Role of Patient-Centered Communication

The importance of PCC is perhaps most apparent in its absence, when communication breaks down or simply does not occur. One study of patients who had recently undergone cancer treatment found approximately 1 in 4 believed something had gone wrong in their care.7 These patients revealed that a majority of problematic events involved communication breakdowns.

Related to information exchange, patients reported

- not receiving information they needed when they needed it (for instance, about treatment options),

- receiving inaccurate information (for instance, a wrong diagnosis), or

- having their reports of symptoms ignored.

Patients also reported problems with relational communication, perceiving cold and uncaring communication from their providers.

Importantly, patients felt these communication breakdowns caused harm—most commonly emotional harm and damage to the provider-patient relationship, but in some cases also physical harm, life disruption, or financial harm. Perhaps most striking was the finding that communication breakdowns were sometimes as harmful from the patients’ perspective as breakdowns in medical care.

A subsequent survey of cancer survivors8 found that approximately 1 in 5 identified a specific communication breakdown during their cancer care. Of these, approximately half involved problems with information exchange, and approximately one quarter involved problems with fostering the relationship. Less frequently reported but also noted were deficits in helping patients with difficult emotions and decision-making. These breakdowns caused patients distress and negatively impacted their overall care experience.

This research and related studies suggest that patients often do not proactively speak up about breakdowns in care, including about communication breakdowns. This makes it all the more important to use strategies to actively reach patients to solicit their perspective on and experiences with communication over the course of cancer care.

Assessment is the first step in identifying whether or where improvements are needed and in preventing the harms that can result when communication falls short.

For more information about communication breakdowns and the role of PCC, see the following:

- Patients’ and family members’ views on patientcentered communication during cancer care. Mazor KM, Beard RL, Alexander GL, Arora NK, Firneno C, Gaglio B, Greene SM, Lemay CA, Robinson BE, Roblin DW, Walsh K. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(11):2487-2495. doi: 10.1002/ pon.3317.

- Toward patient-centered cancer care: patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Greene SM, Lemay CA, Firneno CL, Calvi J, Prouty CD, Horner K, Gallagher TH. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1784-1790. doi: 10.1200/ JCO.2011.38.1384.

- Encouraging patients to speak up about problems in cancer care. Mazor KM, Kamineni A, Roblin DW, Anau J, Robinson BE, Dunlap BS, Firneno C, Gallagher TH. J Patient Saf. 2018; doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000510.

- Cancer survivors’ experiences with breakdowns in patient-centered communication. Street Jr RL, Spears E, Madrid S, Mazor KM. 2019. Psycho-Oncology. 2019;28(2):423-429. doi: 10.1002/pon.4963.

Reliable and valid measures of PCC are essential for conducting communication research. Communication can be measured using a variety of methods, including:

- Patient self-report

- Clinician self-report

- Observational methods.

RTI International and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill developed a patient report measure, the Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care (PCC-Ca), which is based on the National Cancer Institute (NCI) conceptual model of PCC.

The purpose of this measure is to assess PCC in 6 core domains:

- Exchanging information

- Making decisions

- Fostering healing relationships

- Enabling patient self-management

- Managing uncertainty

- Responding to emotions

Researchers and practitioners can use the PCC-Ca for surveillance, quality monitoring, assessment, and intervention evaluation.

This instrument is available in both a long form (36 items) and a short form (6 items) and is easy to score. The User Guide is publicly available in both English and Spanish.

Development of the PCC-Ca

The PCC-Ca was developed and evaluated by a multidisciplinary team that included communication experts, survey methodologists, clinicians, and patients. The process aimed to develop survey questions that reliably and validly capture the 6 core functions of PCC. This included the involvement of a patient advocacy group, Fight Colorectal Cancer, and a multidisciplinary panel of stakeholders throughout the measurement development process to ensure the survey questions

- captured aspects of PCC important to patients; and

- that the questions meet the needs of potential end users, including researchers, healthcare organizations, and health professionals.

For a full description of the development of the PCC-Ca, see the following:

- Engaging patient advocates and other stakeholders to design measures of patient-centered communication in cancer care. Treiman K, McCormack L, Olmsted M, Roach N, Reeve BB, Martens CE, Moultrie RR, Sanoff H. Patient. 2017;10(1):93-103. doi: 10.1007/s40271- 016-0188-6

- Psychometric evaluation and design of patientcentered communication measures for cancer care settings. Reeve BB, Thissen DM, Bann CM, Mack N, Treiman K, Sanoff HK, Roach N, Magnus BE, He J, Wagner LK, Moultrie R, Jackson KD, Mann C, McCormack LA. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(7):1322-1328. doi: 10.1016/j. pec.2017.02.011.

The steps in developing the PCC-Ca include the following:

- Literature review and formative research with colorectal cancer patients and clinicians to identify measurement domains

- Review of existing survey items to determine any that could be used or adapted

- Develop new survey items following recommendations for survey item development15

- Cognitive interviews with patients to evaluate patients’ ability to understand and provide valid answers to the PCC questions.

- Pilot test the instrument to establish the reliability and validity of the PCC-Ca. The pilot test involved 501 adult colorectal cancer patients.

- Psychometric evaluation of the PCC items to design the final versions of the PCC-Ca-36 and PCC-Ca-6 measures. The psychome tric evaluation used a single-time-point assessment of the psychometric properties, including reliability (internal consistency) and construct validity

Conversations with Researchers

Hear from PCC researchers in this video, A Conversation with the Researchers. Three experts in patient-centered communication and measurement development discuss their research and share guidance for using the PCC-Ca for surveillance, quality monitoring, assessment, and intervention evaluation.

Opportunities

- To inform quality improvement initiatives aimed at improving patient-centered care and communication.

- To diagnose potential problem areas in PCC identified through other means. The findings from patient surveys— such as Press Ganey and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS)—can identify groups of patients with lower satisfaction levels or clinical teams that receive poorer ratings. Medical records also can identify issues in quality of care that may be attributed, in part, to shortcomings in patient-clinician communication, such as poor compliance and overuse or underuse of services.

- To evaluate interventions designed to improve patient-clinician communication. PCC assessment can be conducted pre and post interventions.

- To provide feedback to clinicians and clinical teams on patient perceptions of patient-clinician communication.

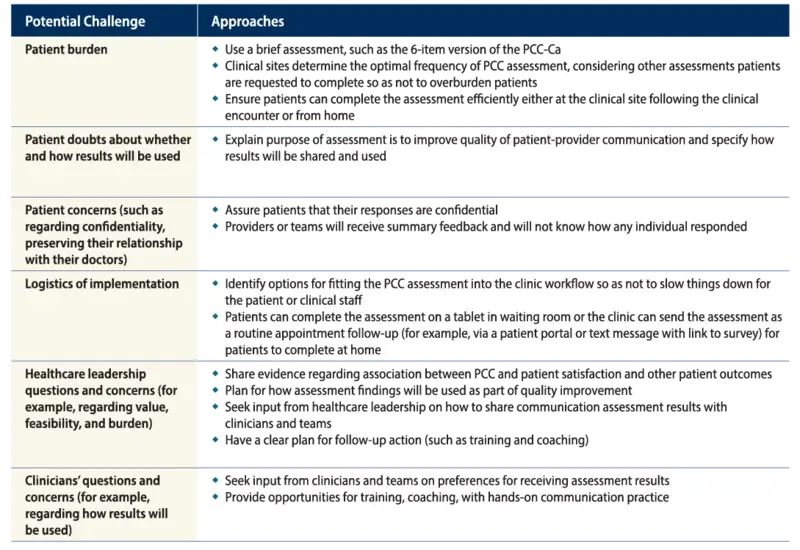

Addressing Challenges to PCC Assessment in Clinical Settings

Clinicians and healthcare leaders value the importance of PCC and PCC assessment to identify areas for improvement. Patients want to provide feedback both to improve their own care experience and to “pay it forward” to improve the experience of future cancer patients.6 However, challenges exist to implementing PCC assessment in cancer care settings.

- Street RL, Jr., Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:295–301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015

- Arora NK, Weaver KE, Clayman ML, Oakley-Girvan I, Potosky AL. Physicians’ decision-making style and psychosocial outcomes among cancer survivors. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:404–412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.004

- Street RL, Jr., Tancredi DJ, Slee C, et al. A pathway linking patient participation in cancer consultations to pain control. Psychooncology. 2014;23:1111-1117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.3518

- Robinson JD, Hoover DR, Venetis MK, Kearney TJ, Street RL, Jr. Consultations between patients with breast cancer and surgeons: a pathway from patient-centered communication to reduced hopelessness. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:351-358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2699

- Trudel JG, Leduc N, Dumont S. Perceived communication between physicians and breast cancer patients as a predicting factor of patients’ health-related quality of life: a longitudinal analysis. Psychooncology. 2014;23:531-538. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.3442

- Mazor KM, Beard RL, Alexander GL, et al. Patients’ and family members’ views on patient-centered communication during cancer care. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2487–2495 .http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.3317

- Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Greene SM, et al. Toward patient-centered cancer care: patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1784–1790. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.38.1384

- Street RL, Spears E, Madrid S, Mazor KM. Cancer survivors’ experiences with breakdowns in patient-centered communication. Psychooncology. 2018;28:423-429. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.4963

- Mazor KM, Kamineni A, Roblin DW, et al. Encouraging Patients to Speak up About Problems in Cancer Care. J Patient Saf. 2018;Publish Ahead of Print. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000510

- Mazor KM, Street Jr RL, Sue VM, Williams AE, Rabin BA, Arora NK. Assessing patients’ experiences with communication across the cancer care continuum. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:1343-1348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.004

- Street RL, Jr., Gordon H, Haidet P. Physicians’ communication and perceptions of patients: is it how they look, how they talk, or is it just the doctor? Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:586–598. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.036

- . Roter D, Larson S. The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS): utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:243–251. http://dx.doi.org/S0738399102000125

- Street RL, Jr., Millay B. Analyzing patient participation in medical encounters. Health Commun. 2001;13:61–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327027HC1301_06

- Gallagher TJ, Hartung PJ, Gerzina H, Gregory SW, Merolla D. Further analysis of a doctor–patient nonverbal communication instrument. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:262-271.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.008

- Aday LA, Cornelius LJ. Designing and conducting health surveys: a comprehensive guide. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2006.

Read the complete "Advancing Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: A Toolkit for Researchers and Practitioners" in PDF format.

Access the PCC-Ca Instrument

The PCC-Ca is now available in Spanish to support research about the communication experiences of Spanish-speaking patients. The PCC-Ca team is excited to share this publicly-available, easy-to-use-tool with the hope of improving patient-physician communication, and ultimately health outcomes for people battling cancer.