It’s been more than two decades since the Nature, Wealth & Power (NWP) framework was developed, and seven years since it was last updated. Recent RTI efforts examine whether NWP remain a helpful way of addressing our planet’s evolving challenges.

“The more things change, the more they stay the same,” the adage goes. But the past few years have been a time of such dramatic global shifts—in action on climate change, urbanization, and the effects of an unprecedented pandemic—that we wondered if that was true for our work in natural resources management.

When NWP was first proposed in 2002, it was focused on rural Africa, where centuries of natural resource extraction were almost entirely decoupled from the needs and interests of the surrounding communities. It called attention to the fact that environmental mismanagement, rural disenfranchisement, and poverty are all interconnected, and referred to access and control over natural resources as “the bread and butter issue on which democracy must deliver.”

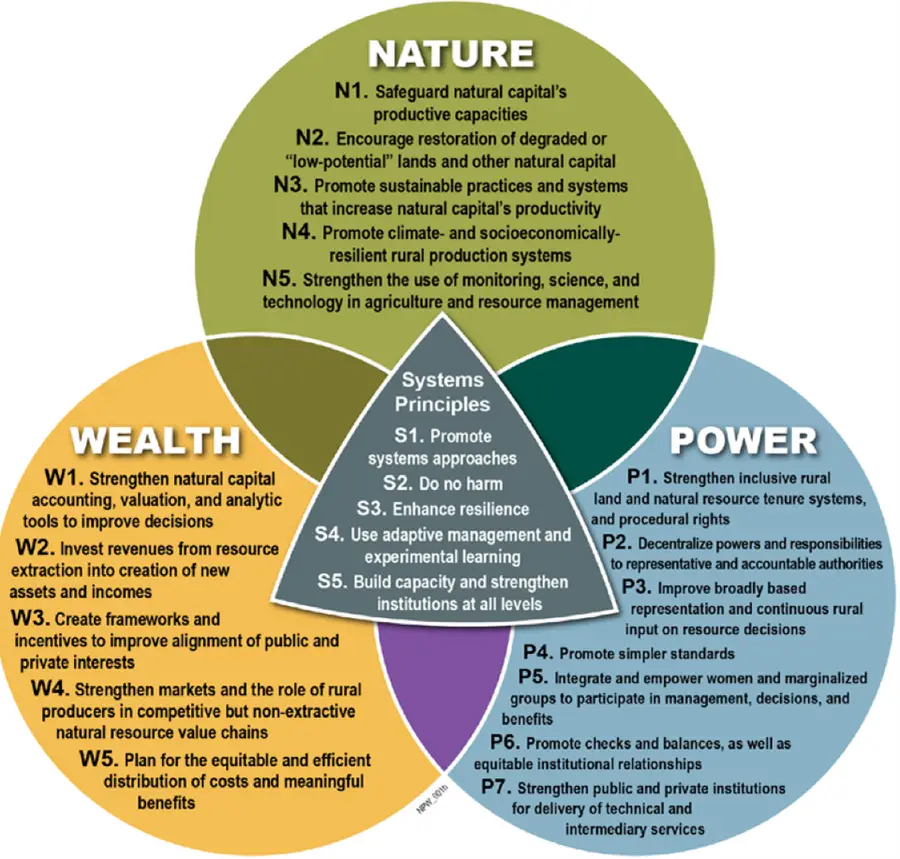

The NWP framework was updated in 2013, broadening its regional applications outside of Africa, heightening its scope beyond the project level, and accounting for changes in, among other things, private sector engagement. It was summarized by what scholar Hilary Faxon called “the best Venn diagram since 5th grade.”

“NWP has grown from niche idea to compelling theory,” Faxon wrote in 2014. “If it can become the foundation of standard development practice, the planet and its poor will be better for it.”

But over time, even as projects continued to use the framework, it seemed to slip out of the mainstream lexicon of development giants.

So, this past year, we initiated an internally funded effort to determine whether NWP is still relevant. Is the framework still useful in addressing what seems like ever-more complex problems?

Nature, Wealth & Power in Action

To answer these questions, our research examined the NWP framework against the latest literature and project experiences and held focus group discussions with current and former international development professionals, including USAID staff and individuals who helped write the original framework. We also looked to RTI’s USAID-funded work in Nigeria and Tanzania, as well as a nature-based solution project in Indonesia, to see how the NWP approach was working.

As part of the USAID Promoting Tanzania's Environment, Conservation, and Tourism (PROTECT) Project, we found that applying the NWP Nature principle of “engaging local communities in data collection” was instrumental to local protection efforts; civil society organizations were collecting and managing conservation data to inform future strategies and plans, make decisions, engage stakeholders, and resolve conflict. In one area, beach management units successfully advocated district leaders for reef closures, allowing the ecosystem to recover and octopus harvests to double within three months.

We saw that NWP’s Power dimension—including the principle of decentralizing power to accountable institutions—was shaping effective programming in Nigeria. Here, the USAID Nigeria Effective Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (E-WASH) program enabled more inclusive decision-making and representation at Niger state’s State Water Board, which made reforms that benefitted 25,000 people with improved access to basic water supply and began tracking its water wastage.

And in Indonesia, the world’s largest registered nature-based carbon emission reduction project is being managed by a private business in keeping with the NWP Wealth principle of aligning public and private interests. The Katingan Mentaya Project is helping to protect over 150,000 hectares of vital peatland, supports livelihoods for 34 villages, and generates an average of 7.5 million triple gold certified carbon credits annually. This privately run initiative is creating a business case for biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation.

The Changes We Need Next – Resilience, Climate Change and Updated Norms

Our evaluation was clear: the framework does remain useful and relevant—perhaps even more so as integrated approaches become the norm. But we also think it might be just the right time to consider another update. One that accounts for all the ways our world continues to shake itself up, and all the ways we continue to come together.

A greater resilience focus: Today, there’s a growing emphasis on resilience—a term that previously didn’t carry the gravitas and urgency it does today. Building resilience at the household, community, ecosystem, and even regional level has become a primary focus for groups ranging from city planners to the United Nations, which didn’t propose using a resilience framework for setting Sustainable Development Goals until 2015.

Increased emphasis on climate change: On the heels of the warmest decade ever recorded, we noticed that the threats posed by climate change have become even more dire than predicted. But international collaborative action on climate change has also increased massively, and the U.S. commitment to leading the way on meaningful change has been restored and redoubled.

Updated recognition of international development norms: We found that the development community itself has changed a lot, too. We are increasingly cognizant of the opportunities we miss when we silo ourselves into disparate areas of practice. As a community, we are putting greater focus on learning from our successes and our mistakes. And we’re doing a much better job of truly partnering with the private sector.

As we continue to apply NWP to our day-to-day work with partners around the world, we look forward to contributing – along with our colleagues across organizations, sectors, countries – to bringing the framework into this new decade with all of its associated uncertainties, challenges, and opportunities for a healthier, wealthier, and more stable world.