Knowledge of financial aid—or lack thereof—is one of many hurdles high school students face in successfully pursuing postsecondary education. Perhaps the most important gateway for students to access financial aid is the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), the federal form required to receive Pell grants and student loans. In addition to federal aid, most states require the FAFSA to determine eligibility for state financial-aid programs, and many institutions ask students to file to receive institutional grants and scholarships.

Unfortunately, recent estimates show that one-third of the students who do not file a FAFSA would have been eligible for a Pell grant and other need-based aid, an issue states have attempted to ameliorate through a variety of strategies. Of these, none has garnered as much attention as Louisiana, which in the 2017-18 school year became the first state to require high school seniors to file the FAFSA before graduation. To complement this “FAFSA First” policy, the state offers free assistance to students and parents and provides workshops to high school counselors. In the inaugural year of FAFSA First, the percentage of students filing grew from 51.2% to 77.1%. (These come from the National College Access Network’s FAFSA Tracker and include private high schools.) Due to this dramatic increase, Louisiana’s policy has been lauded as a success, with 13 states having adopted or considered policies linking filing and high school graduation as of this writing.[1]

Aside from Louisiana, Tennessee is the only other state with an annual FAFSA filing rate over 75%, but it takes a different approach to promoting FAFSA completion. Tennessee’s program, called “FAFSA Frenzy,” launched in the 2016-17 school year and shifts responsibility from individual students to schools by disseminating essential resources to high schools across the state. High schools host FAFSA Frenzy events during school hours where computers and volunteers are available to help students complete the notoriously complicated form. These events are intentionally timed to support students in filing their FAFSA prior to the Feb. 1 deadline for the widely popular Tennessee Promise Scholarship.

Both tactics seem to have increased filing rates, but overall percentages obscure when students are submitting the form, a critical factor in both college choice and access to aid. The FAFSA’s complexity makes it difficult for students and their families to access concrete information on how much aid they may receive, which can lead to delayed action. Students who file after February may have already decided whether and where to apply; those with financial concerns who delay filing are more likely to undermatch or even rule out four-year institutions altogether, limiting their postsecondary goals based on incomplete knowledge. Late filing also leads to students missing out on first-come/first-serve programs at both the state and institution level. Moreover, even if state policies are timed for students to apply for state aid, later filing can still disqualify students from financial aid programs at private or out-of-state institutions with earlier deadlines. Overall, early filers are more likely to receive federal, state, and institutional aid, which is particularly troubling given that the neediest dependent students on average file later than their well-to-do counterparts.

If policies linking filing to high school graduation result in large increases in May and June, students may be filing too late for their FAFSAs to be beneficial or even relevant, giving an exaggerated impression of the effects of the policies. We sought to understand whether the different structures of Louisiana’s and Tennessee’s programs (student- versus school-driven, mandated versus capacity-building) impacted the timing of students’ FAFSA completion.

The dataset we used to examine this contains school-level filing data for each state over the 39-week period from the first week of October (when the FAFSA cycle opens) through the end of June. To examine this, we combined data from Federal Student Aid’s weekly FAFSA completion files, the American Community Survey, and the National Center for Education Statistic’s Common Core of Data. This yielded a dataset of school-week observations for every public high school in Louisiana and Tennessee. (Many thanks to Ellie Bruecker and Bill DeBaun for their generous sharing of data and advice. All errors are our own.)

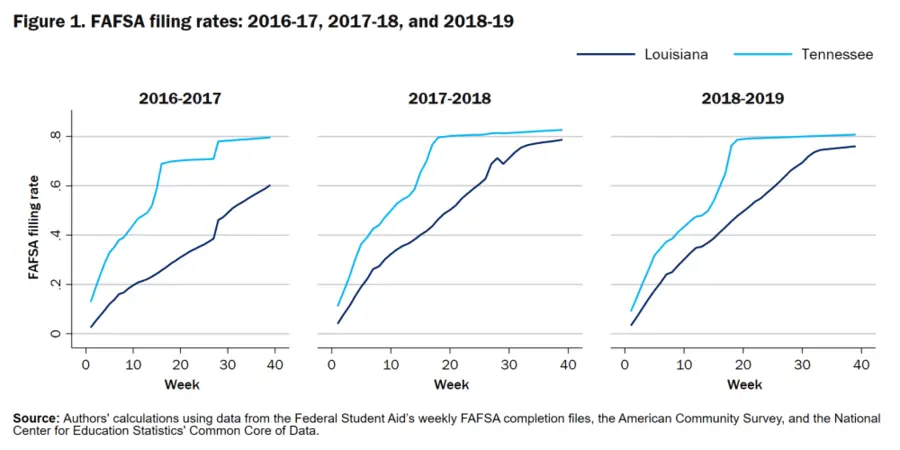

Figure 1 displays the public school filing rate for each state across three academic years. The comparison between 2016-17 and 2017-18, when Louisiana’s FAFSA First was implemented, captures the dramatic increase in the state’s overall filing rates. However, looking more closely at when filings peak, the majority of Tennessee’s filings come before the 20-week mark (mid-February), while Louisiana’s rise more steadily approaching high school graduation.

We extended this analysis with the 2018-19 data by controlling for student demographics, school resources, and socio-economic factors, and examined each state’s predicted effect over time on the percentage of high school seniors filing a FAFSA.[2] In this model, Tennessee’s effect is much greater in early weeks, indicating that increases are driven almost entirely by filers prior to Feb. 1. Louisiana sees a more gradual decrease in its effect across time, with comparatively higher rates late in the filing cycle. In essence, the timing differences observed in the descriptive data in Figure 1 persist in this more rigorous analysis.

These findings suggest that states should consider more carefully timed approaches to increasing FAFSA filing than high school graduation requirements, since late-filing students miss out on many of the benefits that inspired these policies in the first place. Outside of the timing concerns, creating a new administrative hurdle to high school graduation could hinder students from graduating, making us question the need for this requirement at all. While filing as a high school graduation requirement is poised to rapidly diffuse across many states due to its simplicity and Louisiana’s eye-catching results, we recommend that states at least also look to Tennessee as a model for supporting and incentivizing students to file as early as possible to maximize their access to financial aid and postsecondary options.

[1] Texas and Illinois have adopted policies linking FAFSA filing and high school graduation. California, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Oklahoma are currently considering similar policies, per the Education Commission of the States. Michigan and the District of Columbia considered similar policies but opted not to enact them.

[2] These are student-to-teacher ratio, percent free and reduced price lunch, total school enrollment, percent of students who are white, income quartiles of the geographic area, and percent of households with a bachelor’s degree or greater in the geographic area.

This post was originally published by the Brown Center Chalkboard.