In the field of global health, we focus on keeping people healthy throughout their lives—from ensuring pregnant women can attend prenatal checkups, to expanding access to childhood vaccines, to supporting the availability of medicines and care for diseases such as HIV and malaria.

But efforts to improve health around the world do not stop with death.

A recently-developed innovation has the potential to transform how we understand death—and therefore health—globally. Minimally invasive tissue sampling (MITS) can provide a more accurate diagnosis of death than would otherwise be available, helping countries better plan and prioritize their health systems.

Closing the mortality data gap

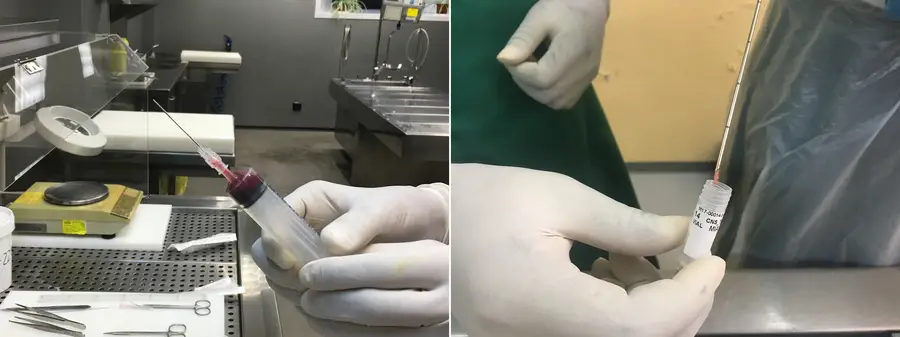

At a MITS training center at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) in Spain, a pathologist delicately inserts a fine needle into a body, collecting a small amount of tissue from the lungs. The sample is carefully placed in a test tube and the process is repeated on other key organs, such as the liver, heart, and brain. The samples are then sent to the lab, where they are analyzed for infectious diseases and malignant tumors.

MITS is relatively new; the technique has been developed, refined, and tested just within the past seven years. But it could help fill an incredibly important data gap that is hindering progress on health worldwide.

In high-income countries, comprehensive mortality records can be analyzed to show disease patterns and their changes over time. Governments and health institutions use this information to plan and prioritize health funding, research, and policies. Unfortunately, high-quality mortality data is often limited in low- and middle-income countries where very few diagnostic laboratory tests and imaging techniques are available, and many facilities lack the resources and infrastructure needed to carry out complete autopsies. This latter complex procedure is also considered culturally unacceptable in some contexts because of its impact on the body.

A less-invasive alternative to complete autopsies, MITS can be performed by trained pathologists or technicians with minimal effect on the appearance of a body.

ISGlobal has worked on initial studies that compare the accuracy of MITS to complete diagnostic autopsy. Findings have been promising, indicating that MITS can frequently identify causes of death as accurately as a full autopsy.

Expanding the use of MITS globally

But health innovations—even if they hold enormous potential—don’t spread overnight.

We’re part of a team facilitating the MITS Surveillance Alliance, a network of researchers and institutions interested in or working on MITS. Funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Alliance’s goal is to help scale up the use of MITS globally. We want more institutions and researchers to have the resources and support they need to use the technique.

This will require standardizing procedures, expanding access to training, and incentivizing researchers and institutions to use MITS. For the latter, the Alliance recently awarded 12 incentive grants to researchers studying MITS in low- and middle-income countries. One study in India will investigate the validity of MITS in determining cause of death among stillbirths and neonates with neurological injuries. A study in Tanzania will look whether MITS can effectively establish cause of death among patients who weren’t hospitalized, or who only stayed in hospital for a short time. Information on these studies will soon be available on the mitsalliance.org website.

Beyond studying the science of MITS, social and behavioral research is also needed to understand whether MITS is acceptable among communities whose cultural practices might not permit autopsies, as well as the steps required for consent within a community and by a family for MITS.

Eventually, political will and investment by governments—particularly ministries of health—will be critical to the expansion of MITS. Support from multilateral health agencies, such as the World Health Organization, will also be important if MITS is to be considered a standard tool in cause of death classification.

Undoubtedly, there is a long road ahead before MITS is considered an everyday tool used to plan the health systems of low- and middle-income countries. More work is needed to continue validating, standardizing, and expanding the technique.

But the result—a more level playing field where all countries will have the high-quality mortality data needed to plan and prioritize their health systems—is worth it. Expanding and standardizing the pathological techniques required for the MITS will also help increase the capacities of local labs and pathologists in other areas, such as cancer diagnosis.

At the end of the day, MITS isn’t just a new scientific method, it’s a global health innovation that will help save and improve lives around the world.