Addressing Plastic Pollution with Chemistry and Communication

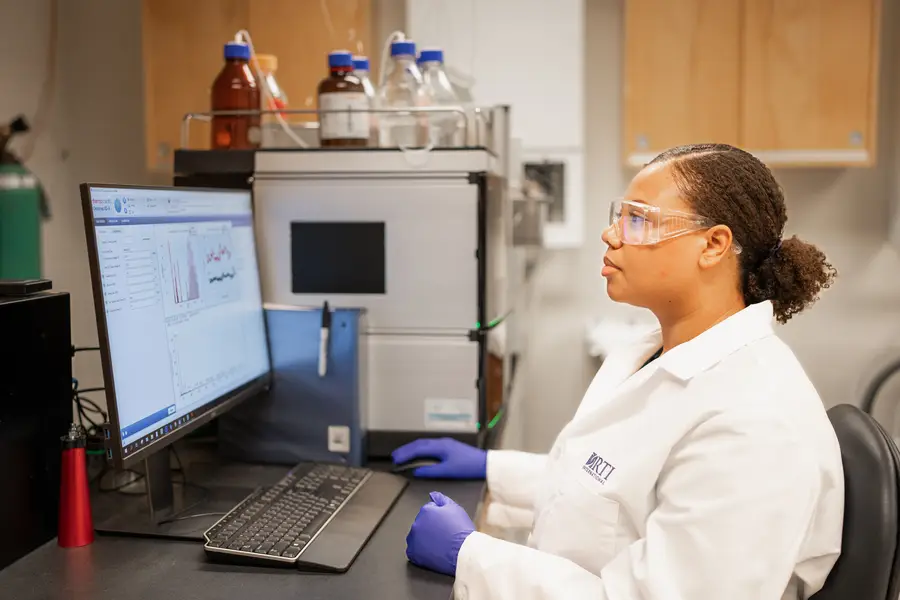

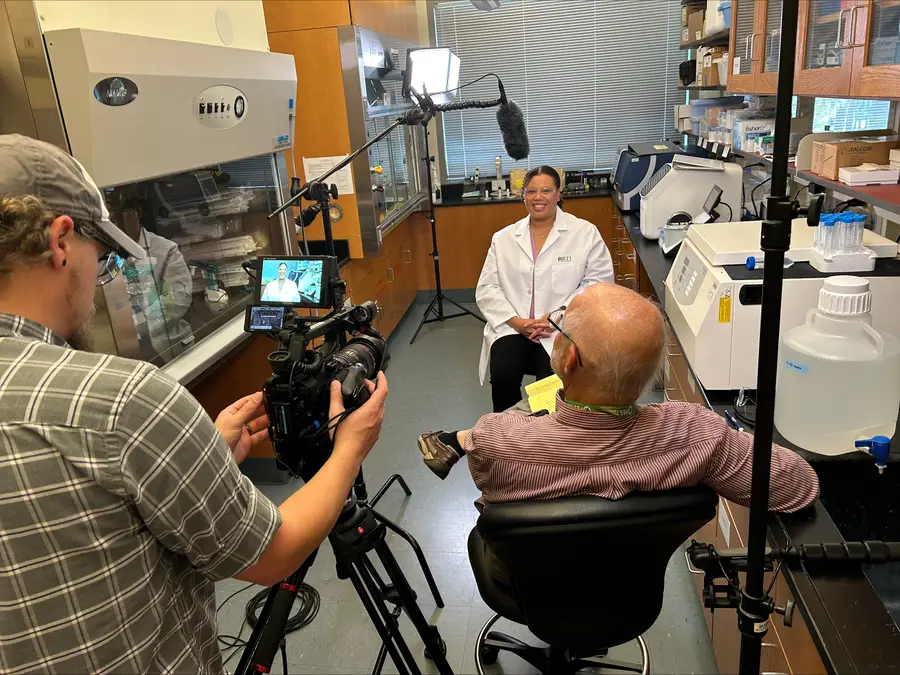

Imari Walker-Franklin is a chemist dedicated to understanding plastic pollution and educating the public.

Imari Walker-Franklin is a chemist dedicated to understanding plastic pollution and educating the public.

One hot day at a summer camp in California, 10-year-old Imari Walker-Franklin was waiting in line to kiss a banana slug.

It was part of a hands-on science lesson on the slug's numbing properties, and Walker-Franklin was dreading her turn. "I think I was the last one in line," she laughed.

She cautiously approached the slug, and as she experienced the numbing for herself, her fear transformed into excitement and wonder. This wonder has fueled her passion for science ever since.

As a teen, Walker-Franklin became interested in both marine science and medicine and initially planned to become a physician. However, while attending the University of California, Berkeley, she had the opportunity to conduct marine science research through the university's Cal NERDS program—a resource and community for STEM students from underrepresented backgrounds. This inspired her to pursue her passion for the ocean and graduate with a marine science degree. "The Cal NERDS program was really a catalyst for that reframing in my mind and career potential that I could do something other than medicine."

Walker-Franklin's first experience with environmental contaminants was during a study abroad research experience in French Polynesia. She noticed that some of the litter washing up on the island's shores came from abroad, and that the lack of a standardized waste management system on the island left residents with limited options including burning their trash in front of their homes.

This experience sparked her interest in plastics and her drive to use environmental engineering to understand plastic pollution, particularly microplastics. Walker-Franklin was nervous to switch fields from marine science to environmental engineering, but she found continued support through the Cal NERDS program.

"They gave me a lot of exposure to other people who look like me, who were doing PhDs or who had finished PhDs, and who had written books. And our professors were doing really awesome, cool things," she said. "That was the main reason why I even considered doing research or even doing a PhD."

She earned her PhD in environmental engineering from Duke University, where she studied the chemicals released from plastic and their effects within aquatic environments.

Alongside her communications efforts, she feels particularly fulfilled as a mentor for undergraduates at North Carolina Central University (NCCU), a Historically Black College and University, through the NCCU-RTI Center for Applied Research in Environmental Sciences (CARES) lab. "A lot of them don't necessarily say that they want to study plastics. They say, 'I want to be a doctor.' 'I want to be a biologist of some kind.' And I say, 'Well, that's great. Let's just talk about research and get you this experience that's slightly different, that's applicable for your future.' And once we start talking about plastics, they realize, 'Oh wow, this is so much bigger than I even thought.'"

While the problem of plastic pollution seems enormous, Walker-Franklin believes that ongoing research, engineering, and policy efforts will have positive results in the next several years. These efforts include designing more sustainable and reusable materials and the United Nations treaty addressing plastic pollution, which is expected to be drafted in 2024.

"I think that there's a lot of hope for the future," she said. "It's not all doom and gloom."