Making the transition from disengagement to deradicalization

Objective:

Identify the factors that provoke people to join fascist, violent, far-right hate groups.

Approach:

We conducted in-depth life-history interviews with former members of these groups, asking them questions about their families, childhoods, education and employment, and how they were recruited into, and mustered the courage to leave, violent, far-right extremist groups.

Impact:

Research indicates that most people join hate groups for a sense of belonging and a sense of power, similar to the way some youth gravitate to gangs. Our goal is to use the research techniques we have developed in our study of former extremist group members and apply them to similar situations, both domestically and around the world.

Since the election of President Barack Obama, white supremacy groups have been increasingly active and visible in the United States. The most notorious example of this trend may be the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville in August of 2017, in which neo-Nazis, neo-Confederates, and members of various militia groups marched with provocative signs and banners and chanted racist and anti-Semitic slogans. The Charlottesville rally (and the concurrent reaction by anti-fascist activists, or “AntiFa”) brought white supremacy back into the national conversation, and served as an unfortunate advertisement for a vile cause.

In the aftermath of Charlottesville, the question naturally presented itself: what provokes people to join racist, violent, far-right hate groups? In 2015, we were contracted by the Department of Justice to perform research on this subject. In collaboration with our partners, Dr. Kathleen Blee of the University of Pittsburgh and Dr. Peter Simi of Chapman University, we contacted dozens of former white supremacists nationwide. We sat down with these people and conducted in-depth life-history interviews, asking them questions about their families, their childhoods, their education and employment, and how they were recruited into, and mustered the courage to leave, various violent, far-right extremist groups.

The Challenge of Identifying Former Members of Hate Groups

Given their understandable reluctance to advertise their past, how does one identify and contact former white supremacists? We obtained our initial leads from Life After Hate (a nonprofit group that helps individuals leave hate groups), media accounts, and prior research on far-right fringe groups. We then used “snowball sampling” to identify additional candidates—simply put, we asked our initial interview subjects if they knew anyone else who would be willing to talk to us.

Talking to people about their attraction to, radicalization in, and exit from violent far-right extremist groups presents several methodological and logistical challenges. Some of the interviewees were concerned that we were either undercover police officers or covert members of their former groups who intended to kill them for retribution. In some cases, many years had elapsed since the interviewees were involved with these organizations, and they had moved on with their lives. In other cases, the exit was more recent, and subjects were still coping with the associated challenges.

Our goal was to ensure that interviewers and interviewees alike were safe and comfortable. A lot of reassurance was involved, and, on our end, we also thoroughly vetted interviewees’ backgrounds and stories, to make sure that their experiences were genuine. The interviews were not conducted in sterile, clinical settings, but often in subjects’ homes or hotel rooms, which helped interviewees feel more relaxed.

What Ex-Members of Hate Groups Have in Common

We conducted interviews lasting 6 to 8 hours with 47 people from 22 states. Among the things we learned are that:

- approximately 40 percent of interviewees grew up in middle-class or upper-middle-class families

- nearly 40 percent of females, and 20 percent of males, had been sexually assaulted as children or adolescents

- around 75 percent of interviewees said they were exposed to racist comments from family members (parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles) as children

Among the experiences interviewees shared were adolescent maladjustment, childhood abuse, and family instability. The totality of these factors made them more vulnerable to recruitment during adolescence and young adulthood; their need to “belong,” to have friends and be socially accepted, made them susceptible to approaches by far-right hate groups. As a general rule, these groups don’t recruit potential members by spouting hateful rhetoric, or suggesting “Hitler was a genius” or “people of color are inferior,” from the get-go. Rather, they acclimate new recruits with fun, seemingly harmless activities like house parties, then gradually ramp up the rhetoric.

This recruitment process leads to a counter-intuitive finding of our study: racial extremism is not necessarily the cause of membership in hate groups, but often a consequence. Prior to their involvement in extremist groups, some individuals may have held racist beliefs that they learned from their families or developed due to social interactions. However, racist ideology is not what drives them to seek membership. Most people join hate groups for a sense of belonging and a sense of power, similar to the way some youth gravitate to gangs. It is only after recruits have been socialized to the group and developed social ties that members are exposed and indoctrinated into the central tenets of organizational hate.

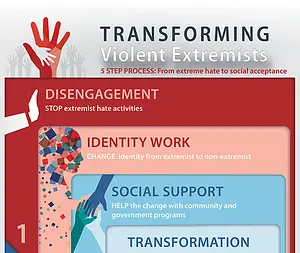

Making the Transition from Disengagement to Deradicalization

Given how all-consuming membership in hate groups can be, how is it that some people muster up the will, and the courage, to leave? It is not a simple process, and it generally happens in two non-consecutive, and sometimes simultaneous stages. Physically leaving the group is called “disengagement;” the social milieu is left behind, but the former member may continue to hold racist beliefs. More important is what we call “deradicalization,” in which the former member recognizes the falsity of the group’s belief system and moves on with his or her life, leaving racist ideology behind.

Our goal is to use the research techniques we have developed in our study of former extremist group members and apply them to similar situations, both domestically and around the world. What is it that makes a young Norwegian teenager susceptible to recruitment by ISIS? How can we prevent vulnerable teens and adults from being recruited into hate or terror groups, and how can we help them to leave? What parallels exist between recruitment and radicalization into hate groups and recruitment into gangs? These are increasingly important issues that cry out for effective techniques and approaches.

- U.S. Department of Justice